One of the most famous narratives in the Hebrew Bible is the tale of three men (angels?) who visit Abraham in Genesis 18. It is a beloved story for many reasons. For Jews, Abraham is a paragon of hospitality, rushing around to make his guests as comfortable as possible. This story exemplifies the virtue of hachnasat orchim, offering hospitality to wayfarers, which according to the Talmud is “greater than welcoming the Divine Presence” (Bavli, Shabbat 127a). For Christians, the story also exemplifies the value of hospitality. The Book of Hebrews says, “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it” (Heb. 13:2). But it has an additional level of meaning; the three divine guests are in fact the three members of the divine Trinity (see Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 56).

According to Gen. 18:1, the location of this story is on the outskirts of Hebron in a place known as Elonei Mamre (אלוני ממרא), which is translated “Oaks of Mamre” or “Terebinths of Mamre”. Presumably this was a well-known grove of trees, where nomads such as Abraham would graze their flocks. This grove is named for Mamre, one of the Amorite chieftains with whom Abraham made an alliance earlier (Gen. 14:13, 24). The grove contains alon (אלון) trees. The alon is the Kermes oak (quercus calliprinos), one of the most common trees indigenous to the Central Hill Country of the Land of Israel, which we looked at in another blog post. Unfortunately, most of the virgin oak groves in the Land of Israel no longer exist due to deforestation over the past few centuries. Here is a photograph of a grove of Kermes oaks found in Turkey.

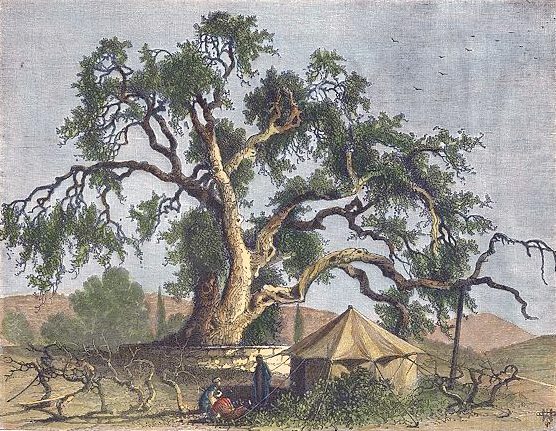

The traditional pilgrimage site that commemorates this biblical narrative is called Hirbet es-Sibta, located not far from Hebron. This site contains a very ancient Kermes oak tree, which pilgrims have visited for centuries. Here is an engraving of the famous tree from 1875.

Known as the “Oak of Abraham” it is located on the grounds of a Russian Orthodox monastery (Abraham’s Oak Holy Trinity Monastery). Sadly, the tree is no longer alive today. Nonetheless, the trunk, which has been propped up with metal rods, still stands:

Let us return to our passage, which communicates a sense of urgency, repeating the verbs “run” (רץ) and “hasten” (מהר) three times each. Upon spotting the travelers walking in the hot sun, Abraham immediately runs out of his tent to greet them. He bows down on the ground before them, the ultimate demonstration of respect. He invites them into his tent, where he washes their feet and invites them to rest in the shade. And then the feast begins. The food that Abraham serves his divine guests is simple fare but freshly prepared in their honor. As we will soon see, it is typical of the food eaten by pastoral nomads in the Middle East. It includes three basic elements that were readily available: bread, meat and cheese. Let’s take a look at each of these.

First, Abraham instructs Sarah to make fresh bread.

And Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Make ready quickly three measures of choice flour, knead it, and make cakes.”

וַיְמַהֵר אַבְרָהָם הָאֹהֱלָה, אֶל-שָׂרָה; וַיֹּאמֶר, מַהֲרִי שְׁלֹשׁ סְאִים קֶמַח סֹלֶת–לוּשִׁי, וַעֲשִׂי עֻגוֹת. (Genesis 18:6)

The typical daily bread eaten by Israelites was made from barley flour. Wheat flour was more tasty but more expensive, as seen here:

But Elisha said, “Hear the word of the Lord: thus says the Lord, Tomorrow about this time a measure of choice meal shall be sold for a shekel, and two measures of barley for a shekel, at the gate of Samaria.” (2 Kings 7:1)

Usually, therefore, wheat flour was reserved for special occasions. The fact that Abraham instructs Sarah to use “choice wheat flour” (kemah solet קמח סלת) indicates the significance of these guests. Likely the bread that Sarah made was similar to what in Arabic is called markuk, a kind of flatbread. It is much bigger than a standard pita and there is no air pocket in the middle. The dough is rolled out very thinly and baked quickly on a hot metal domed griddle (“sadj”) that covers the fire. This type of bread is still popular throughout the Middle East.

Second, Abraham selects an animal for the main course.

Abraham ran to the herd, and took a calf, tender and good, and gave it to the servant, who hastened to prepare it.

וְאֶל-הַבָּקָר, רָץ אַבְרָהָם; וַיִּקַּח בֶּן-בָּקָר רַךְ וָטוֹב, וַיִּתֵּן אֶל-הַנַּעַר, וַיְמַהֵר, לַעֲשׂוֹת אֹתוֹ. (Genesis 18:7)

In the Ancient Near East, for a shepherd to slaughter a calf (Hebrew: ben-baqar בן-בקר, literally the “son of an ox”) was a very big deal. As a pastoral nomad, Abraham did not own real estate (with the notable exception of the tomb he purchases in Gen. 23). His sole property was his livestock, which would have included sheep, goats and a few cows. Typically, on special occasions, a sheep was slaughtered. Cattle were exceptionally prized. Thus slaughtering a calf was quite rare. Clearly Abraham has pulled out all the stops in honor of his guests.

Finally, Abraham serves the men the meal:

Then he took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them; and he stood by them under the tree while they ate.

וַיִּקַּח חֶמְאָה וְחָלָב, וּבֶן-הַבָּקָר אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה, וַיִּתֵּן, לִפְנֵיהֶם; וְהוּא-עֹמֵד עֲלֵיהֶם תַּחַת הָעֵץ, וַיֹּאכֵלוּ. (Genesis 18:8)

How exactly should we conceive of this rather odd meal that contains just three ingredients: curds, milk and the meat of a calf? Where are all the colorful salads that are so typical of Middle Eastern food? What we see here is a basic shepherd feast that has been augmented in honor of these guests. Curds (Hebrew: khema חמאה) refers to a kind of sour cheese made from curdled goat’s milk. The milk is strained through a cheese cloth, which makes it more concentrated. It is known as “labaneh” in Arabic. As of late, this type of cheese has become popular in the West and is known as “Greek yogurt”, as seen here:

Interestingly, the word khema has come to mean “butter” in Modern Hebrew, but this is clearly not what is meant in our passage. Butter requires refrigeration, which is not possible in the desert, whereas labaneh can be stored unrefrigerated for quite some time, if covered in olive oil. Milk (Hebrew: khalav חלב) could be a reference to cow’s or goat’s milk. The meat of the calf was grilled, or cooked in a pot along with the milk. Perhaps we can imagine Abraham serving his guests a dish analogous to the popular Middle Eastern dish known as mansaf. As seen in this photograph, the meat which has been cooked in milk is combined with rice, placed atop the flat-bread, and yogurt is poured over the whole thing.

Something that troubles many readers of this story is the issue of mixing milk with meat. The Torah explicitly states the prohibition against boiling a kid (= baby goat) in its mother’s milk three times (Exod. 23:19, 34:26; Deut. 14:21). Jewish interpreters of the Bible later understood this prohibition to apply to the combination of any dairy and meat products. Therefore, contemporary Jews who keep kosher would never eat a meal such as the one served by Abraham in Genesis 18. How do we solve this problem? One solution is to say that since this story appears before the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai, there was no need yet for Abraham to separate milk and meat. Quite simply, Abraham was not a modern rabbinic Jew! Another, more clever solution is that verse 8 never explicitly mentions the milk and meat being eaten together. What is to prevent us from saying that first they ate the dairy products as an appetizer while the calf was being prepared, and only much later they ate the meat as the main course? Although it would seem as though this meal blatantly violates the rules of kashrut, when the passage is read creatively, the problem can be swept under the carpet.

I love reading and learning about the bible please don’t stop sending me all this information. Sorry I’m not financially able to pay for the studies but take as much knowledge I can many thanks and God bless Madelaine Gunn

Thanks for sharing, specially those hi-resolution images attached.