The Samaritan woman story must be reconsidered. (Too many people feel that there is something missing.)

The Samaritan woman story must be reconsidered. (Too many people feel that there is something missing.)

The chapter that relates the story of Jesus meeting the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well in John 4 begins by setting the stage for what will take place later in Samaria and is rooted in what already by this time in the Gospel’s progress has taken place in Judea. Jesus’ rapidly growing popularity resulted in a significant following. His disciples performed an ancient Jewish ritual of ceremonial washing with water, just as did John the Baptist and his disciples. The ritual represented people’s confession of sin and their recognition of the need for the cleansing power of God’s forgiveness. When it became clear to Jesus that the crowds were growing large, but especially when he heard that this alarmed Pharisees very much, he decided it was time to go to Galilee to continue his ministry (vs.1-3).

(The pictures come from here and here and do not constitute endorsement of any kind)

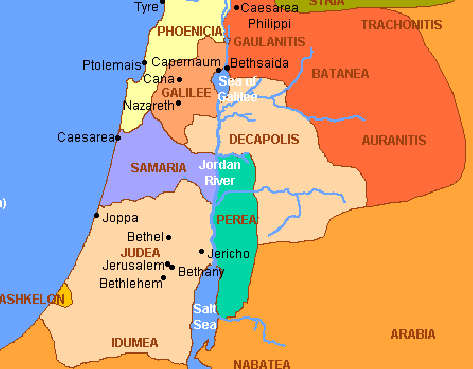

Geography

The text simply says that Jesus “had to go through Samaria” (vs.4). Perhaps, at this point a short geography lesson would be helpful. Samaritan lands were sandwiched between Judea and Galilee. The way around Samaria took twice as long as the three day direct journey from Galilee to Jerusalem because avoiding Samaria required crossing the river Jordan twice to follow a path running east of the river (Vita 269). The way through Samaria was more dangerous because often Samaritan-Jewish passions ran high (Ant. 20.118; War 2.232). We are not told the reason Jesus and his disciples needed to go through Samaria. John simply says that Jesus “had to go” implying that for Jesus this was not ordinary. Perhaps Jesus needed to get to Galilee relatively quickly. But the text gives us no indication that he had a pending invitation to an event in Galilee that he was running late to. Only that he left when he felt an imminent confrontation with the Pharisees over his popularity among Israelites was unavoidable. This was coupled with Jesus’ understanding that the time for such a confrontation has not yet come. In the mind of Jesus the confrontation with the religious powerbrokers of Judea, (and make no mistake about it the leading Pharisees were integral part of such leadership) at this time was premature and that more needed to be done before going to the cross and drinking of the cup of God’s wrath on behalf of his ancient covenant people and the nations of the world. The way Jesus viewed Samaritans and his own ministry to them may surprise us as we continue looking at this story.

We know that Jesus’ movements and activities were all done according to his Father’s will and leading (Jn.5:19). He only did what he saw the Father do. This being the case, we can be certain that Jesus’ journey through Samaria at this time was directed by his Father and so, too, was his conversation with the Samaritan woman.

Jesus’ surprising journey through hostile and heretical territory has a meaning beyond any surface explanation. In a very real sense, God’s unfathomable plan and mission from the time His royal son was eternally conceived in the mind of God, was to bind in redemptive unity all of his beloved creation. Jesus was sent to make peace between God and people as well as between people and people. The accomplishing of this grand purpose began with an uncomfortable encounter between Jesus and those who practically lived next door – the Samaritans.

To explore my new online course “The Jewish Background of the New Testament”, click HERE.

Samaritans

The sources present us with at least two different histories of the Samaritans. One – according to the Israelite Samaritans, and the other – according Israelite Jews. While difficulties exist with the reliability of the ancient documents tainted by the Samaritan-Jewish polemic as well as the late dating of the sources on both sides, some things can nevertheless be established. The Samaritan story of their history and identity would roughly correspond to the following:

The sources present us with at least two different histories of the Samaritans. One – according to the Israelite Samaritans, and the other – according Israelite Jews. While difficulties exist with the reliability of the ancient documents tainted by the Samaritan-Jewish polemic as well as the late dating of the sources on both sides, some things can nevertheless be established. The Samaritan story of their history and identity would roughly correspond to the following:

1) The Samaritans called themselves Bnei Israel (Sons of Israel).

2) Samaritans were a sizable group of people who believed themselves to be the preservers of the original religion of ancient Israel. The name Samaritans literally from Hebrew means The Keepers (of original laws and traditions). Though it is difficult to speak of concrete numbers Samaritan population at the time of Jesus was comparable to those of the Jews and included large diaspora.

3) Samaritans believed that the center of Israel’s worship ought not to have been Mt. Zion, but rather Mt. Gerizim. They argued that this was the site of the first Israelite sacrifice in the Land (Deut.27:4) and that it continued to be the center of the sacrificial activity of Israel’s patriarchs. This was the place where blessings were pronounced by the ancient Israelites. Samaritans believed that Bethel (Jacob), Mt. Moriah (Abraham) and Mt. Gerizim were the same place.

4) The Samaritans essentially had a fourfold creed: 1) One God, 2) One Prophet, 3) One Book and 4) One Place.

5) The Samaritans believed that the people who called themselves Jews (Judea-centred believers in Israel’s God) had taken the wrong path in their religious practice by importing novelties into the Land during the return from the Babylonian exile.

6) Samaritans proper rejected the pre-eminence of the Davidic dynasty in Israel. They believed that the levitical priests in their temple were the rightful leaders of Israel.

Now that we have made a partial summary of the undisputed by other side history and beliefs of the Samaritans, let us turn to the Jewish version of that same history. This record essentially comes to us from the two Talmuds and its reading of the Hebrew Bible, Josephus and the New Testament.

1) Samaritans were a theologically and ethnically mixed people group. They believed in One God. Moreover, they associated their God with the God who gave the Torah to the people of Israel. The Samaritans are genetically related to the remnants of the Northern tribes who were left in the land after the Assyrian exile. They intermarried with Gentiles who were relocated to Samaria by the Assyrian Emperor. This act of dispossession and transfer from their homeland was done in a strategic attempt to destroy the people’s identity and to prevent e any potential for future revolt.

2) In the Jewish rabbinical writings, Samaritans are usually referred to by the term “Kuthim.” The term is most likely related to a location in Iraq from which the non-Israelite exiles were imported into Samaria (2 Kings 17:24). The name Kuthim or Kuthites (from Kutha) was used in contrast to the term “Samaritans” (the keepers of the Law). The Jewish writings emphasized the foreign identity of the Samaritan religion and practice in contrast to the true faith of Israel that they saw especially in the later period as Rabbinical Judaism.[1] Rabbinic portrayals of the Samaritans were not exclusively negative.

3) According to 2 Chronicles 30:1-31:6, the claim that the northern tribes of Israel were all exiled by the Assyrians and therefore those who occupied the land (Samaritans) were of a non-Israelite origin upon closer reading is rejected by the Hebrew Bible. This passage states that not all of the people from the northern kingdom were exiled by the Assyrians. Some, perhaps confirming Samaritan version, remained even after the Assyrian conquest of the land in the 8th century BCE.

4) The Judea-centred Israelites (the Jews) believed that not only did the Samaritans choose to reject the words of the prophets regarding pre-eminence of Zion and Davidic dynasty, they also deliberately changed the Torah itself to fit their theology and heretical practices. One of the insights that can be gained from comparing the two Pentateuch’s, the Torah of the Samaritans and the Torah of the Jews. The Samaritan text reads much better than the Jewish one. In some cases, the stories in the Jewish Torah seem truncated, with wandering logic and unclear narrative flow. In contrast, the texts of the Samaritan Torah seem to have a much smoother narrative flow. On the surface, this makes the Jewish Torah problematic. Upon further examination, however, this could lead to an argument for the Samaritan Pentateuch being a latter revision or editing of the earlier Jewish text. Based on this and other arguments, we agree with the Jewish view in arguing that Samaritan Torah is a masterful and theologically guided revision of the early Jewish corresponding texts.

To explore my new online course “The Jewish Background of the New Testament”, click HERE.

The Encounter

In describing the encounter, John makes several interesting observations that have major implications for our understanding of verses 5-6:

In describing the encounter, John makes several interesting observations that have major implications for our understanding of verses 5-6:

“So he came to a town in Samaria called Sychar, near the plot of ground Jacob had given to his son Joseph. Jacob’s well was there, and Jesus, tired as he was from the journey, sat down by the well. It was about the sixth hour.”

First, John mentions the Samaritan town named Sychar. It is not clear if Sychar was a village very near Shechem or Shechem itself is in view.[2] The text simply calls our attention to a location near the plot of ground Jacob gave his son Joseph. Whether or not it was same place, it was certainly in the same vicinity at the foot of Mt. Gerizim. While this is interesting and it shows that John was indeed a local, knowing the detailed geography of Ancient Roman Palestine, it is no less important, and perhaps even more significant, that the Gospel’s author calls the reader’s attention to the presence of a silent witness to this encounter – the bones of Joseph. This is how the book of Joshua talks about that event:

The reason for this reference to Joseph in verse 5 will only become clear when we see that the Samaritan woman suffered in her life in a manner similar to Joseph. If this reading of the story is correct, than just as in Joseph’s life, unexplained suffering was endured for the purpose of bringing salvation to Israel, so the Samaritan woman’s suffering in hew life led to the salvation of the Israelite Samaritans in that locale (4:22).

John continues: “Jacob’s well was there, and Jesus, tired as he was from the journey, sat down by the well. It was about the sixth hour” (vs. 6). It has been traditionally assumed that the Samaritan woman was a woman of ill repute. The reference to the sixth hour (about 12 PM) has been interpreted to mean that she was avoiding the water drawing crowd of other women in the town. The biblical sixth hour was supposedly the worst possible time of the day to leave one’s dwelling and venture out into the scorching heat. “If anyone were to come to draw water at this hour, we could appropriately conclude that they were trying to avoid people,” the argument goes.

We are, however, suggesting another possibility. The popular theory views her as a particularly sinful woman who had fallen into sexual sin and therefore was called to account by Jesus about the multiplicity of husbands in her life. Jesus told her, as the popular theory has it, that He knew that she had five previous husbands and that she was living with her current “boyfriend” without the bounds of marriage and that she was in no shape to play spiritual games with Him! In this view, the reason she avoided the crowd is precisely because of her reputation for short-lived family commitments.

First, 12PM is not yet the worst time to be out in the sun. If it was 3PM (ninth hour) the traditional theory would make a little more sense. Moreover, it is not at all clear that this took place during the summer months, which could make the weather in Samaria irrelevant all together. Second, is possible that we are making too much out of her going to draw water at “an unusual time”? Don’t we all sometimes do regular things during unusual hours? This doesn’t necessarily mean that we are hiding something from someone. Third, we see that the daughters of the priest of Median were helping him to satisfy the thirst of his animals at around the same time of day, when people supposedly do not come to wells (Exodus 2:15-19).

When we read this story, we can’t help but wonder how it is possible in the conservative Samaritan society that a woman with such a bad track record of supporting community values caused the entire village to drop everything and go with her to see Jesus, a “heretical to Samaritans” Judean would be prophet. The standard logic is as follows. She had led such a godless life that when others heard of her excitement and new found spiritual interest they responded in awe and went to see Jesus for themselves. This rendering, while still possible, seems unlikely to the authors of this book and seems to read in much later theological approaches into this ancient story that had its own historic setting. We are persuaded that reading the story in a new way is more logical and creates less interpretive problems than the commonly held view.

Let us take a closer at this passage.

“When a Samaritan woman came to draw water, Jesus said to her, ‘Will you give me a drink?’ (His disciples had gone into the town to buy food.) The Samaritan woman said to him, ‘You are a Jew and I am a Samaritan woman. How can you ask me for a drink?’ (For Jews do not associate with Samaritans.)” (vs.7-9)

In spite of the fact that to the modern eye the differences were insignificant and unimportant, Jesus and the nameless Samaritan woman were from two different and historically adversarial people, each of whom considered the other to have deviated drastically from the ancient faith of Israel. In short, their families were social, religious and political enemies. This was not because they were so different, but precisely because they were very much alike.

According to the traditional perspective, the Samaritan woman probably recognized that Jesus was Jewish by his distinctive Jewish traditional clothing. Jesus would have most certainly worn ritual fringes in obedience to the Law of Moses (Num.15: 38 and Deut. 22:12). Since Samaritan men observed the Mosaic Law too, it is likely that the Samaritan woman’s former husbands and other men in her village also wore the ritual fringed garment. The Samaritans’ observance of the Mosaic Law (remember Samaritans means the “keepers” of the Law and not the people that lived in Samaria) was according to their own interpretation and differed from the Jewish view on some issues, but it is important to remember that they were more like rival siblings to the Israelite Jewish community than like unrelated strangers. We continue reading:

“‘If you knew the gift of God and who it is that asks you for a drink, you would have asked him and he would have given you living water.’ ‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘you have nothing to draw with and the well is deep. Where can you get this living water? Are you greater than our father Jacob, who gave us the well and drank from it himself, as did also his sons and his flocks and herds?’ Jesus answered, ‘Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the water I give him will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life.’ The woman said to him, ‘Sir, give me this water so that I won’t get thirsty and have to keep coming here to draw water.’ He told her, ‘Go, call your husband and come back.’ ‘I have no husband,’ she replied. Jesus said to her, ‘You are right when you say you have no husband. The fact is, you have had five husbands, and the man you now have is not your husband. What you have just said is quite true.’ ‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘I can see that you are a prophet. Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, but you Jews claim that the place where we must worship is in Jerusalem.’”

This passage has been often interpreted as follows: Jesus initiates a spiritual conversation (vs.10). The woman begins to ridicule Jesus’ statement by pointing out Jesus’ inability to provide what he seems to offer (vs.11-12). After a brief confrontation in which Jesus points out the lack of an eternal solution to the woman’s spiritual problem (vs. 13-14), the woman continues with a sarcastic attitude (vs.15). Finally, Jesus has had enough and he then forcefully exposes the sin in the woman’s life – a pattern of broken family relationships (vs.16-18). Now, cut to the heart by Jesus’ all knowing ex-ray vision, the woman acknowledges her sin in a moment of truth (vs.19) by calling Jesus a prophet. But then, as every unbeliever usually does, she tries to avoid the real issues of her sin and her spiritual need. She begins to talk about doctrinal issues (vs.20) in order to avoid dealing with the real issues in her life. Though this may not be the only way this text is usually reads, it does follow generally negative view of the Samaritan woman.

Because this popular interpretation presupposes that the woman was particularly immoral, it sees the entire conversation in light of that negative viewpoint. We would like to recommend a wholly different trajectory for understanding this story. Though it is a not an airtight case, this alternative trajectory seems to be a better fit for the rest of the story and especially its conclusion.

To explore my new online course “The Jewish Background of the New Testament”, click HERE.

Rereading the Story

As was suggested before, it is possible that the Samaritan woman was not trying to avoid anybody at all. But, even if she was, there are explanations for her avoidance other than feeling so guilty about her sexual immorality. For example, as you well know people don’t want to see anyone when they are depressed. Depression was present in Jesus’ time just as it is present in people’s lives today. Instead of assuming that the Samaritan woman changed husbands like gloves, it is just as reasonable to think of her as a woman who had experienced the deaths of several husbands, or as a woman whose husbands may have been unfaithful to her, or even as a woman whose husbands divorced her for her inability to have children. Any one of these suggestions and more are possible in this instance.

As was suggested before, it is possible that the Samaritan woman was not trying to avoid anybody at all. But, even if she was, there are explanations for her avoidance other than feeling so guilty about her sexual immorality. For example, as you well know people don’t want to see anyone when they are depressed. Depression was present in Jesus’ time just as it is present in people’s lives today. Instead of assuming that the Samaritan woman changed husbands like gloves, it is just as reasonable to think of her as a woman who had experienced the deaths of several husbands, or as a woman whose husbands may have been unfaithful to her, or even as a woman whose husbands divorced her for her inability to have children. Any one of these suggestions and more are possible in this instance.

It is important to note that to have five successive husbands was unheard of in ancient society, especially a conservatives one like the Israelite Keepers of the Law (Samaritans). This fact even caused some ancient and modern commentators to erroneously suggest that this encounter was not historical, but metaphorical. ‘Since Samaritans represented Gentiles and therefore the unreasonable situation of having five husbands should have given a clue to the reader that this is not a real story and not a real woman’ went their argument. In that society, unless the woman was wealthy, adopting her non-committal life-style was an economic impossibility. Since it was not her servant but she herself who went to draw water, we conclude that she was probably not wealthy and therefore simply could not afford the sort of lifestyle that we have endowed her with throughout the centuries of Christian interpretation. Without even considering other possibilities as viable options, those who have taught us, and those who have taught them, have consistently portrayed this woman in a wholly negative light. This we believe is unnecessary.

If we are correct in our suggestion that this woman was not a particularly “fallen woman,” then perhaps we can connect her amazingly successful testimony to the village with John’s unexpected but extremely important reference to the bones of Joseph. It is noteworthy that for Gentile and even “Jewish” hypothetical readers of this Gospel, the place of burial of Joseph’s bones would not be as important, though still significant, as it would have been to the Israelite Samaritans, since the bones of the Patriarch also link God’s presence with the vicinity of Mt. Gerazim and the Holy city of Shechem. When we hear that the conversation takes place next to Joseph’s bones, immediately we are reminded about Joseph’s story and his mostly undeserved suffering. As you remember, only part of Joseph’s sufferings were self-inflicted. Yet in the end, when no one saw it coming, the sufferings of Joseph turned out to be events leading to the salvation of the world from starvation.

Now consider the connection with Joseph in more detail. Shechem was one of the cities of refuge where a man who had killed someone without intention was provided a safe heaven. (Josh. 21:20-21) As inhabitants of Shechem were living out their lives in the shadow of the Torah’s prescription they were no doubt keenly aware of the unusual status of grace and God’s protective function that was allotted to their special city. They were to protect people who were unfortunate, whose lives were threatened by avenging family members, but were actually not guilty of any intentional crime worth the punishment threatened.[4]

Joseph was born into a very special family where grace and salvation should have been a characteristic description. Jacob, the descendent of Abraham and Isaac, had 11 other sons, whose actions, instead of helping their father to raise Joseph, ranged from outbursts of jealousy to a desire to get rid of their spoiled but “special” brother forever. But there was more. It was in Shechem that Joshua assembled the tribes of Israel, challenging them to abandon their former gods in favour of YHWH and after making the covenant with them, buried Joseph’s bones there. We read in Josh. 24:1-32:

“Then Joshua assembled all the tribes of Israel at Shechem. He summoned the elders, leaders, judges and officials of Israel, and they presented themselves before God… But if serving the LORD seems undesirable to you, then choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve, whether the gods your forefathers served beyond the River, or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land you are living. But as for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.”… On that day Joshua made a covenant for the people, and there at Shechem he drew up for them decrees and laws. 26 And Joshua recorded these things in the Book of the Law of God. Then he took a large stone and set it up there under the oak near the holy place of the LORD… 31 Israel served the LORD throughout the lifetime of Joshua and of the elders who outlived him and who had experienced everything the LORD had done for Israel. And Joseph’s bones, which the Israelites had brought up from Egypt, were buried at Shechem in the tract of land that Jacob bought for a hundred pieces of silver from the sons of Hamor, the father of Shechem. This became the inheritance of Joseph’s descendants.

It is interesting that the place for this encounter with the Samaritan woman was chosen by the Lord of providence in such a beautiful way: an emotionally alienated woman who feels unprotected while she lives in or near the city of refuge, is having a faith-founding, covenant conversation with the Renewer of God’s Covenant – God’s Royal Son Jesus. She does so at the very place where the ancient Israelites renewed their covenant in response to God’s words, sealing them with two witnesses: 1) the stone (Josh.24:26-27), confessing with their mouths their covenant obligations and faith in Israel’s God and 2) the bones of Joseph (Josh.24:31-32) whose story guided them in their travels.

In a sense, the Samaritan woman does the same thing as the Ancient Israelites in confessing to her fellow villagers her faith in Jesus as the Christ and covenant Savoir of the world. We read in John 4:28-39:

“Come, see a man who told me everything I ever did. Could this be the Christ?” They came out of the town and made their way toward him… Many of the Samaritans from that town believed in him because of the woman’s testimony…”

The connection between Joseph and the Samaritan woman does not end there. We recall that earlier Joseph received a special blessing from his father at the time of Jacob’s death. It was a promise that he would be a fruitful vine climbing over a wall (Gen. 49:22). Psalm 80:8 speaks of a vine being brought out of Egypt whose shoots spread throughout the earth, eventually bringing salvation to the world through the true vine. In John 15:1 we read that Jesus identifies himself as this true vine and just as Israel of old, Jesus was also symbolically brought out of Egypt (Matt.2:15). In his conversation with the Samaritan woman, Jesus – the promised vine in Jacob’s promise to Joseph – is in effect climbing over the wall of hostility between the Israelite Jews and Israelite Samaritans to unite these two parts of His Kingdom through His person, teaching and deeds. In a deeply symbolic fashion this conversation takes place at the very well that was built by Jacob to whom the promise was given!

Now that we have reviewed some relevant Old Testament symbolism, let us now reread this story through a different lens. It may have gone something like:

Jesus initiates a conversation with the woman: “Will you give me a drink?” His disciples had gone into town to buy food. The woman feels safe with Jesus because, not only is he not from her village; he does not know about her failed life or even how depressed she may have felt for months. In her view, he was part of a heretical, though related, religious community. Jesus would have had no contact with the Israelite Samaritan leaders of her community. He was safe. This openness of the woman to Jesus is very similar to Christian workers seeking outside counselling for their family problems. People they know and love are nice, but can also be dangerous. Who knows?! They may leak information that in some cases may end the worker’s ministerial career. So in difficult cases, Christian ministry workers usually opt for paid counselling specialists who are independent and unconnected to their churches and ministries. The specialist is safe. It’s his or her job. That’s all. In that sense Jesus was safe. He was not a Samaritan and a Jew.

The problem here was not simply that Jesus was a Jew and she a Samaritan; their peoples, their fathers and grandfathers, were bitter enemies in the religious and the political arenas. Both peoples considered the other to be imposters. Scholars point out, appealing to the Babylonian Talmud, such rabbinic Talmudic statements as “Daughters of the Samaritans are menstruants from the cradle” and therefore any item that they would handle would be unclean to the Jew (bNidd. 31b) and “It is forbidden to give a woman any greeting” (bQidd. 70a). It is important that we be aware of methodological problems when appealing to the Talmud. The Babylonian Talmud was codified and edited much later than were the Gospels (early 200 C.E. vs. early 600 C.E.). Therefore we must be cautious in using the Talmud to explain the much earlier Gospels. Not only was it written much later, but also, as is widely agreed, it was not recognized as the sole or even major representative of Jewish teaching until sometime between the 6th-8th centuries. In other words, in contrast to today, it represented only the elite and marginal rabbinical classes and not the whole Jewish community’s way of thinking. All of this is to say that the do-not-greeting-a-woman rule may not have been at all a rule practiced by Jesus, the Jew and therefore cannot be uncritically used in interpretation. On the other hand the reference to the Samaritan women going through menstruation periods from their birth, while obviously mythical does fit perfectly with other things we know about the deep-seated hatred between Samaritans and Jews. But even with that a good level of caution within interpretive freedom should be exercised.

Jesus responds: “If you knew the gift of God and who it is that asks you for a drink, you would have asked him and he would have given you living water.” It is important that we picture the woman. She was not laughing; she was having an informed, deeply theological and spiritual discussion with Jesus. This was a daring attempt to ascertain truth that was outside her accepted theological framework and surely would not pass the test of cultural sensibilities of “faithful” Samaritans. She takes issue issue with Jesus, precisely because she take the word of God (Samaritan Torah) seriously:

“‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘you have nothing to draw with and the well is deep. Where can you get this living water? Are you greater than our father Jacob, who gave us the well and drank from it himself, as did also his sons and his flocks and herds?’ Jesus answered: ‘Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the water I give him will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life.’ The woman said to him, ‘Sir, give me this water so that I won’t get thirsty and have to keep coming here to draw water.’”

After the above interaction, which strikes a familiar chord for the Christian who has experienced the life giving power of Jesus’ presence and spiritual renewal, Jesus continues the conversation. Jesus lets the nameless Samaritan woman know that He understands her troubles much more fully than she thinks, by showing her that he is aware of all the pain and suffering she endured in her life.

“He told her, ‘Go, call your husband and come back.’ ‘I have no husband,’ she replied. Jesus said to her, ‘You are right when you say you have no husband. The fact is, you have had five husbands, and the man you now have is not your husband. What you have just said is quite true.’”

Remember the seemingly obscure reference to Joseph’s bones being buried near this very place where the conversation took place? At the beginning of the story, John wanted us to remember Joseph. He was a man who suffered much in his life; but whose suffering was ultimately used for the salvation of Israel and the known world. Under Joseph’s leadership, Egypt became the only nation that acted wisely by saving grain during the years of plenty and then being able to feed others during the years of famine. It is highly symbolic that this conversation took place in the presence of a silent witness – the bones of Joseph. God first allowed terrible physical, psychological and social injustice to be done to Joseph, but he then used this suffering to greatly bless those who came in contact with Joseph. Instead of reading this story in terms of Jesus nailing the immoral woman to the cross of the standard of God’s morality, we should read it in terms of God’s mercy and compassion for the broken world in general, and marginalized Israelites in particular.

According to the popular view, it is at this point, convicted by Jesus’ prophetic rebuke, that the woman seeks to change the subject and avoid the personal nature of the encounter by engaging in non-important theological controversy. The problem is that these matters are un-important only to the modern reader. They were of very real concern for ancient readers especially those whose home was in Roman Palestine. Therefore, let us consider an alternative interpretation that, having seen Jesus’ intimate knowledge of her miserable situation and his compassionate empathy, the woman feels secure enough to also break tradition and to climb over the wall of forbidden associations. She makes a statement that invites Jesus’ commentary on a matter having to do with the key theological difference between the Jews and Samaritans.

“‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘I can see that you are a prophet. Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, but you Jews claim that the place where we must worship is in Jerusalem.’

As you may remember the Samaritans were Mt. Gerazim-centered Israelites in their understanding of the Pentateuch (Torah), while the Jews were Mt. Zion-centered in their interpretation of essentially the same body of literature, admittedly with occasional variations. This question seems trivial to a modern Christian who usually thinks that what is really important is that one can say: “Jesus is in my life as a personal Lord and Savoir”. But while this question does not bother anyone today, it was a major issue for the Israelite Samaritans and Israelite Jews and by extension the Jewish Jesus and the Samaritan woman. Indeed this deeply theological and spiritual conversation was a very important intersection on the road of human history, because of the tremendous impact of the Christian message on the entire world ever since this encounter took place.

With fear and trepidation the Samaritan woman, putting away her feeling of humiliation and bitterness towards the Jews, posed her question in a form of a statement. She got from Jesus something that she definitely did not expect to hear from a Judean prophet:

“Jesus declared, ‘Believe me, woman, a time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. You Samaritans worship what you do not know; we worship what we do know, for salvation is from the Jews. Yet a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for they are the kind of worshipers the Father seeks. God is spirit, and his worshipers must worship in spirit and in truth.’”

In our reading therefore the Samaritan woman’s question reflected a good, honest, and righteous assumption that Jesus’ ministry and arrival in Samaria had rendered already obsolete. In the book of Hebrews (Heb.12:1-24) the author addressed the believing community. He stated that the greatness of faith in Israel’s God through Jesus the Messiah must provoke them to a far greater response than the ones enshrined in Jewish tradition. He urged believers to persevere in the faith as follows:

“Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith… You have not come to a mountain that can be touched and that is burning with fire… But you have come to Mount Zion, to the heavenly Jerusalem, the city of the living God. You have come to thousands upon thousands of angels in joyful assembly, to the church of the firstborn, whose names are written in heaven. You have come to God, the judge of all men, to the spirits of righteous men made perfect, to Jesus the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel.”

The basic argument here is that responsibility to observe the New Covenant is much greater than any level of covenant responsibility that was encountered by the people of God in the past. Therefore keeping this covenant is essential in spite of difficult circumstances. The author appeals to everything that is greater: Jesus is greater than the great Moses, the New Covenant is greater than the great Old Covenant, the blood of the righteous man (Jesus) is greater than the blood of the righteous Abel. Basically, the greater the covenant, the greater is the responsibility. One of the arguments included within the overall comparison in the book of Hebrews is that the heavenly Mt. Zion is better and greater that the great earthly Zion.

The basic argument here is that responsibility to observe the New Covenant is much greater than any level of covenant responsibility that was encountered by the people of God in the past. Therefore keeping this covenant is essential in spite of difficult circumstances. The author appeals to everything that is greater: Jesus is greater than the great Moses, the New Covenant is greater than the great Old Covenant, the blood of the righteous man (Jesus) is greater than the blood of the righteous Abel. Basically, the greater the covenant, the greater is the responsibility. One of the arguments included within the overall comparison in the book of Hebrews is that the heavenly Mt. Zion is better and greater that the great earthly Zion.

Jesus had already stated that the center of earthly worship was to be relocated from physical Jerusalem to the heavenly, spiritual Jerusalem concentrated in Himself when he spoke to Nathaniel. Please, allow us to explain. The incident is related in John 1:50-51.

“Jesus said, ‘You believe because I told you I saw you under the fig tree. You shall see greater things than that.’ He then added, ‘I tell you the truth, you shall see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.’”

Jesus invoked the great Torah story of Jacob’s dream of the angels of God ascending and descending on the Holy Land of Israel where he was sleeping (Gen.18:12). He said to Nathaniel that very soon the angels would be ascending and descending, not on Bethel (in Hebrew – House of God) which Samaritans believed to be identified with Mt. Gerizim, but upon the ultimate House of God – Jesus himself (Jn.1:14).

The official Samaritan religion, as far as we know, did not include any prophetic writings, at least as far as we know from much latter sources writing about Samaritans. “The woman said, ‘I know that “Messiah” (called Christ) is coming. When he comes, he will explain everything to us.”” Then Jesus declared, “I who speak to you am he.” (vs. 25-26) We read in Deut.18:18-19:

“I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their brothers; I will put my words in his mouth, and he will tell them everything I command him. If anyone does not listen to my words that the prophet speaks in my name, I myself will call him to account.”

Though a later Samaritan text speaks of a Messiah-like figure Taheb (Marqah Memar 4:7, 12), the Samaritans of Jesus’ time only expected a great teacher-prophet. The “Messiah” as the King and Priest was an Israelite Jewish, not an Israelite Samaritan concept as far as we know. For that reason the reply of the Samaritan woman shows that this was not an imaginary or symbolic conversation (he will explain to us everything). In view of this, it seems that now the woman graciously used Jewish terminology to relate to Jesus – the Jew.[5] Among Samaritans this was not usual. Just as Jesus was choosing to climb the wall of taboos, so now was the Samaritan woman. The story of this encounter “gives guidelines about how to deal with wounds and divisions, especially those of long-standing… in the Samaritan pericope he is presented as a reconciler of ancient enemies.” We will consider this theme in this book’s application final chapter in this book entitled – the Call.

The story quickly switches to the return of the disciples, their reaction and commentary-like interaction with Jesus. This interchange is sandwiched between the encounters with the Samaritan woman and the men of her village. The disciples were surprised at seeing him conversing with the Samaritan woman, but no one challenged him about the inappropriateness of such an encounter.

27 Just then his disciples returned and were surprised to find him talking with a woman. But no one asked, “What do you want?” or “Why are you talking with her?” 28 Then, leaving her water jar, the woman went back to the town and said to the people, 29 “Come, see a man who told me everything I ever did. Could this be the Christ?” 30 They came out of the town and made their way toward him. 31 Meanwhile his disciples urged him, “Rabbi, eat something.” 32 But he said to them, “I have food to eat that you know nothing about.” 33 Then his disciples said to each other, “Could someone have brought him food?” 34 “My food,” said Jesus, “is to do the will of him who sent me and to finish his work. (John 4:27-39)

While it is possible that disciples were surprised he was alone with the woman the general context of the story seems to point us in the direction that disciple’s response had to do him conversing with Samaritan woman instead. Leaving behind her jar, the woman rushed to town to tell her people about Jesus. Posing an important question to them could this be the one whom Israel has been awaiting for long? Speaking as he was in the context of the encounter Jesus points out to his disciples that what he was doing was God’s will pure and simple. That doing of the will of his Father gave him his divine life energy. This divine energy enabled him to continue his work. We continue to reading:

“Do you not say, ‘Four months more and then the harvest?’ I tell you, open your eyes and look at the fields! They are ripe for harvest. Even now the reaper draws his wages; even now he harvests the crop for eternal life, so that the sower and the reaper may be glad together. Thus the saying ‘One sows and another reaps’ is true. I sent you to reap what you have not worked for. Others have done the hard work, and you have reaped the benefits of their labour.’”

In these verses, Jesus has challenged his disciples. The writer of the Gospel of John is challenging his readers to consider the crop that is ready for harvesting. It is almost certain that the disciples of Jesus thought the spiritual harvest pertained to the Jewish community alone. Jesus challenged them to look outside their box to the neighbouring heretical and adversarial community for the harvest – a field that they had not considered until this encounter. The significance of Jesus’ commentary on the encounter was not to highlight the importance of evangelism in general but rather to bring attention to the fields that were previously unseen or thought of as unsuitable for the harvest.

While Jesus no doubt was conversing with his followers about suitability of teaching Samaritans God’s ways, he heard voices from the crowd approaching him from a distance. The faithful witness of this gospel, describes it like this:

“Many of the Samaritans from that town believed in him because of the woman’s testimony, ‘He told me everything I ever did.’ So when the Samaritans came to him, they urged him to stay with them, and he stayed two days. And because of his words many more became believers. They said to the woman, “We no longer believe just because of what you said; now we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this man really is the Saviour of the world.” (vs.39-42)

To explore my new online course “The Jewish Background of the New Testament”, click HERE.

Honest Hermeneutics

Interpreting the Bible is difficult task. It is as difficult as interpreting anything else in life. We bring our past, our preconceived notions, our already formed theology, our cultural blind spots, our social standing, our gender, our political views, and many other influences to the interpretation of the Bible. In short, all that we are in some way determines how we interpret everything. This does not imply that the meaning of the text is dependent on its reader. The meaning remains constant. But the reading of the text does differ and is dependant on all kinds of things surrounding the interpretive process. In other words what a reader or listener gets out of the text can differ greatly from person to person.

One of the biggest handicaps in the enterprise of Bible interpretation has been an inability to recognize and admit that a particular interpretation may have a weak spot. The weak spot is usually determined by personal preferences and heartfelt desires to prove a particular theory regardless of the cost. We, the authors, consider that having an awareness of our own blind spots and being honestly willing to admit problems with our interpretations when they exist, are more important than the intellectual brilliance with which we argue our position.

One opportunity to exercise an honest approach is when commentators recognizes that there is something in their interpretation that does not seem to fit with the text and the commentators do not quite know how to explain it. What we feel can be legitimately suggested as a challenge to our reading of the story of the Samaritan woman are the words the Gospel author places on her lips when she tells her fellow villagers about her encounter with Jesus. She says: “He told me everything I ever did.” What would have matched our interpretation perfectly is if her words had been, “He told me everything that happened to me” or better yet “was done to me”.

There are several viable options for resolving this problem. Some of the options include grammar issues and hypothetical the existence of an earlier Aramaic version of the Gospel of John. While allowing for these possibilities, the authors consider that the best response is to refer to a manuscript of the Gospel of John that has the phrase in a shorter version. In this manuscript, the woman’s words do not end with “He told me everything I ever did,” but with “he told me everything”. These words could refer to either self-inflicted or other-inflicted circumstances and do not by itself present any kind of problem for our reading of the story.

The next question would be why this manuscript’s reading should be preferred to the commonly used one. In order to explain this, we will need to introduce a very important biblical studies tool that may be unfamiliar to many readers. However, many of you have encountered the results of applying this tool many times by people that work with new Bible translations. For example, many modern Bibles put brackets in place of John 8:1-11 and mention that the earliest and the most reliable manuscripts do not contain the beloved story of the woman caught in adultery who was brought to Jesus (Mark 16:9-20 is handled the same way). This story may be true and may have been transmitted orally before being incorporated into the text of John, but it must be acknowledged that, even if this story is true, it must have been only later inserted by a copyist. The interpretive tool that was used here is called textual criticism. The nomenclature is misleading, since the text is not being criticized, but rather compared with other manuscripts and analyzed. In other words textual criticism refers to a careful analysis of a text in comparison to other texts with the express goal of determining the earlier and more precise manuscripts.

Textual criticism considers various ancient manuscripts, since we do not have a single original of any biblical book, in order to determine the text that would be as close to the original as possible. Textual criticism uses all recent and older manuscripts discoveries. Though to some Christians, proposing the relevance of such a method might imply unbelief, we are persuaded that when used responsibly this method can be a significant tool in the hands of honest, capable and especially believing interpreters of the ancient texts. How can this scientific method help?

One example is the general principle that textual criticism uses to determine which manuscript is earlier, a principle that could be called “priority of the shorter manuscript.” A shorter manuscript is preferred because the ancient scribes were more likely to expand the text they were copying than make it shorter. Expansion of the text was done with some liberty in the ancient world, in contrast to modern readers’ general discomfort with such a practice, a discomfort shared by the authors of this book.

It was of course still possible that the longer text (in our case, “He told me everything I ever did”) was the original. But the textual critical method argues that, in general, the opposite was the case. The shorter text is most likely to have been the original (in our case “He told me everything”) and only later was the text expanded by a scribe who felt that the text would be improved and its meaning clarified if he added the “I ever did” ending. If we are correct in our understanding and the context of the story argues in our favour, than it would be fair to say that the Christian scribe in his desire to help the reader with improving the flow of this narrative, actually ended up sending the reader in a different interpretive direction.

Conclusion

In democratic courts we follow the principle “innocent until proven guilty.” In a sense we are declaring here to the court of our readers that we believe we have presented enough evidence to show “the presence of reasonable doubt.” We are arguing that the charges of “immorality and not seeking spiritual truth” should be dropped against the Samaritan woman. The reasons are the lack of evidence and the presence of other likely scenarios that could explain the interaction between her and Jesus in a more satisfactory way. We argue that this story should serve as an example and a call to reconsider the message of the Holy Scriptures in its historical contexts and with greater willingness to think outside agreed traditions that may ultimately have nothing to adequately support them. Earlier in the chapter we stated that we are not presenting an airtight case. We are, however, suggesting a possible alternative to the usual interpretation. We believe our alternative is a more responsible one. Our claims are therefore modest, but remain challenging. It was Mark Twain who said “Loyalty to a petrified opinion never yet broke a chain or freed a human soul.”

To explore my new online course “The Jewish Background of the New Testament”, click HERE.

© By Eli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg, Ph.D.

[1] It is a mistake to think that the main reason for Jewish antipathy toward the Samaritans was racial. Judaism has always had a strong tradition of Gentile conversions where the converted Gentiles became full-fledged Jews and were accepted by the community. One notable example of such an attitude is Rabbi Akiva who was not ethnically Jewish (neither he nor his parents went through a formal conversion to Judaism). It is not the non-Jewish DNA that was responsible for the Jewish antipathy. The adversarial relationship was largely religious in nature. The political component of rivalry should also not be overlooked when considering the reasons for the negative relationship between Samaritans and the Jews. For example, when Alexander the Great was passing through the region, he is reported to have paid tribute to Israel’s God in the Temple on Mt. Gerizim and not on Mt. Zion.

[2] This may have been a case of textual corruption where the end letter (“mem” was replaced by “resh”) was confused by a scribe.

[3] See Calum M. Carmichael. Marriage and the Samaritan Woman. New Testament Studies 26 (1980): 332-346.

[4] See also Ps. 60:6-7 and Ps.108:7-8 twice in verbatim repetition we are told that Ephrem is God’s protective gear – helmet.

[5] Samaritans called their Temple for “Zeus the friend of strangers” thereby avoiding trouble under Antiochus IV (2 Macc. 6:2) which cemented even more the negative feelings between Jews and Samaritans. Deut.27:3 in MT has Mt. Ebal as place where first alter was to be built, while Samaritan Pentateuch has Mt. Gerazim in its place. It is not clear whether MT changed the identity of the mountain because of Anti-Samaritan views, or vice versa.

Dr Eli, yes this was helpful. I now see the meaning in John 21 (alive until Christ comes). Your studies are also teaching me a great deal about unity (1 Corinthians 12).

So glad to hear. Would you pass info about our blog to all your friends? Dr. Eli

I keep rerunning the words “eternal life” (4:13) . I notice the Samaritan woman seems to connect eternal life with living on earth (my interpretation is she is thirsty for righteousness, not confessing sins repeatedly). I had separated the meaning of the words eternal life into two different categories— heaven (eternal life) and—how to live life (life in the spirit). I am left to wonder what the word eternal life was intended to mean (in Hebrew of course).

Kat, hi! Biblical eternal life is not at all divorced from living on Earth eternally. See John 21. Hope this help. The New Heavens and New Earth are merged together in response to the several petitions of the Lord’s prayer. The Kingdom come, etc. … ON EARTH as it is in heaven.

Thanks: She was not a sinner, but a woman of sorrow.

The woman answered, “I have *no* husband.”

Jesus said unto her, “….he whom you now have is *not thy husband*..” Which might put her in the category of Anna of the Temple (Luke2:36-37), and fits with her influence.

Also Jesus saith unto her, “Woman, believe me, the hour comes, when you shall *in this mountain*, yet *at Jerusalem*, worship the Father.” The hour of destruction came for both places within a generation. I understand Mt Gerazim was rebuilt in 135 then destroyed 484. He spoke literally.

Please, SpigielOnline – they have a nice article about the Samaritans – http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/new-research-shows-that-jerusalem-may-not-be-the-first-temple-a-827144.html it also gives you the dates for Temple rebuilding and destruction.

I have just read the comment on the samaritan woman, and it has recall to my mind the OT. when the land is dealed by Joshua: “from this point is for Benjamin….; there, is mentioned Semer with a plot,” the name, according this dealing would be Semer and not Shimron, or is this a wrong translation/interpretation of the name?

Please, send me the exact reference and I will take a look. Dr. Eli

According your request: 1 Kings 16:24, there appears “Omri bought the hill of Semer, and built on there, and called the city Samaria, because the name of the owner of the hill”.

Thank you, Gustavo. OK… so here we go. This is the origin of Samaria and Samarians, but not Samaritan or Samaritans (this comes from a different root). LeShmor – to Guard. Therefore Samaritans are the Guardians (of the ancient Israelite traditions). They are not Shamronim (in Hebrew) but Shomrim.

Very refreshing commentary on the Samaritan woman passage. I really love how the connection with Joseph was developed and her anguish and suffering which was proposed in your commentary is quite real in my opinion. I think this is a very real possibility given the social expectations and possible stigma of the ancient patriarchal society. An example of another woman who had many husbands comes to mind in considering this passage. This is the prayer of Sarah, Tobit’s wife before she became his wife. She was also tormented by her predicament, but totally innocent and pure according to her earnest prayer.

3:7 It came to pass the same day, that in Ecbatane a city of Media Sara the daughter of Raguel was also reproached by her father’s maids; 3:8 Because that she had been married to seven husbands, whom Asmodeus the evil spirit had killed, before they had lain with her. Dost thou not know, said they, that thou hast strangled thine husbands? thou hast had already seven husbands, neither wast thou named after any of them. 3:9 Wherefore dost thou beat us for them? if they be dead, go thy ways after them, let us never see of thee either son or daughter. 3:10 Whe she heard these things, she was very sorrowful, so that she thought to have strangled herself; and she said, I am the only daughter of my father, and if I do this, it shall be a reproach unto him, and I shall bring his old age with sorrow unto the grave. 3:11 Then she prayed toward the window, and said, Blessed art thou, O Lord my God, and thine holy and glorious name is blessed and honourable for ever: let all thy works praise thee forever. 3:12 And now, O Lord, I set mine eyes and my face toward thee, 3:13 And say, Take me out of the earth, that I may hear no more the reproach. 3:14 Thou knowest, Lord, that I am pure from all sin with man, 3:15 And that I never polluted my name, nor the name of my father, in the land of my captivity: I am the only daughter of my father, neither hath he any child to be his heir, neither any near kinsman, nor any son of his alive, to whom I may keep myself for a wife: my seven husbands are already dead; and why should I live? but if it please not thee that I should die, command some regard to be had of me, and pity taken of me, that I hear no more reproach. 3:16 So the prayers of them both were heard before the majesty of the great God. (Tobit 3:7-16)

I thought I would offer this parallel from the period literature for consideration. This is something that came to mind as I was reading the commentary, so I decided to share.

Dear Peter, very very helpful thank you! I am going to incorporate this into the full article. Thank you for your contribution. Eli

You are most welcome.

Your article combining Jewish ritual on confession of sin with the Samaritan woman has helped me find my “missing link” between the words confession of sin, forgiveness, and Romans 7:24. I have always thought forgiveness wanted me to come back again and again.

Wonderful! Glad to hear. Dr. Eli

An interesting perspective. Christians traditionally do focus especially hard on the sins of women, as did the lleaders in Jesus’ day who dragged in the woman caught in adultery,”in the very act,” but neglected to bring in the adulterer. Bathsheba has also long been villified, yet if you follow the power, she was truly a stolen lamb sacrificed, as Nathan the Prophet described her to King David.

I am so glad that you brought this up. You see that story was not part of the original Gospel. We know that because all earliest manuscripts do not contain it. Why did it ended up in the Gospel of John then? Well… because of misinterpretation of the Samaritan woman story by a scribe or the school to which the particular copying scribe belonged to!

A scribe who knew about this oral tradition (woman caught in the act and a wonderful story about Jesus’ response to those who accused her) sought to insert it in a good place somewhere in the Gospels (not finding any good place in the synoptic gospels), he thought that the Gospel of John could be the appropriate host. He failed to see that Samaritan woman was not the sinner par excellence he imagined her to be. So, he made a mistake.

I agree about Bathsheba too. In the patriarchal and monarchic society one can hardly speak of justice and equality for women. That equality, even veneration, began with the Gospels. Mary in particular is the case and the point.

I am so glad to see your various perspectives re Samaritan Israelites, influence from Alan Crown, etc. I have a theory that John 7:53-8:11 pericope adulterae was inserted by a later redactor specifically to parallel with the John 4 woman in order to provide another semeion, that of Jesus’ fulfillment of the prophesied messianic reunification of both north and south Israel (e.g., Ezek 37), metaphorically represented by two sinful women (like Oholah and Oholibah in Ezek 23). Even if you are correct, the redactor may not have agreed with you. But the main thing is to see Samaritans as Israelites. Keep up the great work!

Thanks, James. This is very interesting. Hm… I think by the time redactors worked on this they already missed the point, probably inserting this by mistake at this point without much (NORTH/SOUTH) intention. But if you turn out to be right, I would be even happier. The Book the Jewish Gospel of John will be out in 2 months. The whole book is about this perspective. So stay tuned. Eli

[…] Once you watch this video that recasts the woman from sinner to saint (or at least a God-fearing Samaritan woman), please, read my article “Reconsidering Samaritan Woman” here. […]

I have read the article, however, I really do not know the difference between Samaritans and Samarians. My guess is that Samarians are people from the Ur of ancient times. Or maybe they are just people that lived north of Benjamin. However, I had a Jewish tour guide from Eli in Samaria. She said that 2000 years ago the term Samaritan was a term used for common people in Israel who were not religious or in religious government. They could have been ethnically Jewish or otherwise.

The tour guide was unfortunetly mistaken… it seems. Make sure that you read my posts that may be clearer (http://iibsblogs.wpengine.com/samaritan-jewish-commentary-on-gospel-of-john/) Please, look for the following:

For Whom, by Who, from Where and When? (Important)

Judean Christian Mission to the Israelite Samaritans

Rethinking Israelite Samaritans and their Diaspora

A Niche Market for John’s Gospel

Are We Talking About the Same “Jews”?

The key is this Samarians are all kinds of people that lived in Samaria, Samaritans are literaly from Hebrew – the Gurdians – SHOMRIM not SHAMRONIM

Please, continue with this research read more. This is a trully neglected topic in both Jewish and New Testament Studies.

The Jewish view of the Samaritans comes from II Kings 17:1-3 and 18:9-12. In II Cor. 29-31 Hezekiah has just become king and refurbishes the temple then has the Passover inviting Israel to come. This is his first or second year at best to reign. The northern kingdom is taken out finally in Hezekiah’s 6th year as you see it given in the Kings verses.REading all those chapters we see that it says all were taken out and replaced with Assyrians who are not familiar with anything about the land.

I would say the priest that was sent back to teach the people about the G-d of Israel was certainly well versed in the scriptures and did a good job of teaching the people. Having lived with people who readily adopt the customs of other cultures and when they received the scriptures immediately identified themselves with the people in those scriptures, I can see where this also could have happened in this situation.

I have visited the museum the Samaritans have and they feel it proves they have all 12 tribes represented among them.

It seems there is hardly any group on G-d’s green earth that wouldn’t like to replace the Jews. But of course in time G-d’s justice and reign over the affairs of man will straighten us all out.

You presenting the Judean view of Samaritans that is that Samaritans and Samarians are one and the same thing. Samaritans say: No way! Before we go on further, please, read carefully a very informative article about Samaritan-Jewish split by late Prof. Alan Crown http://wp.me/p3iCCe-pK I trust that would help a lot. Write me back when you are done and we can continue this once that piece of the historical puzzle is in place.

Blessings, Dr. Eli

In the lesson on the Samaritan Woman you mentioned a book entitled, “The Call”. Is it possible that I could purchase this book from you?

http://www.JewishGospelofJohn.com