A legitimate question may be asked: Why would even consider seeking to answer the question of John’s use of “the Jews” by looking at the Gospel of John in the context of Samaritan beliefs and interactions (though not only)? In brief, the answer is on account of the importance given to the Samaritan mission by the early Jesus-believing Jews:

A legitimate question may be asked: Why would even consider seeking to answer the question of John’s use of “the Jews” by looking at the Gospel of John in the context of Samaritan beliefs and interactions (though not only)? In brief, the answer is on account of the importance given to the Samaritan mission by the early Jesus-believing Jews:

In Acts 1: 8, we read Jesus’ post-resurrection instructions to the disciples not to leave Jerusalem. He told them “… you shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the remotest part of the earth.” While it has been traditionally assumed that Samaria simply is a geographical half-way point between Jewish Judea and the Gentile ends of the earth.

In Acts 8: 25 we read about the extensive preaching of the Gospel in the Samaritan villages: “… they started back to Jerusalem, and were preaching the gospel to many villages of the Samaritans”.

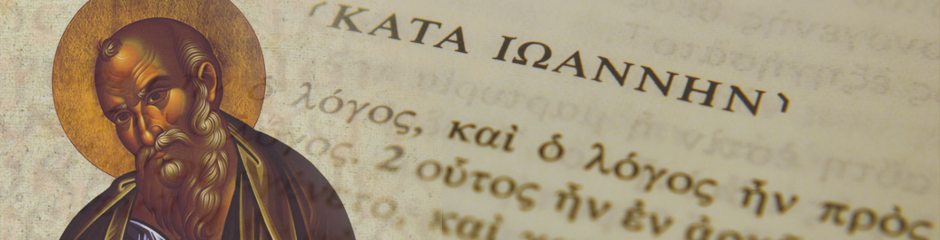

In Acts 8: 14 we are told that the apostles Peter and John were sent to the Israelite Samaritans.[10] The fact that John was actually in Samaria and was commissioned by the rest of the apostles to go and inspect the Samaritan’s reception of faith in Jesus is important for our argument. Interestingly enough, the book of Acts places the apostle John, who from early times was held to be the author of this gospel, at the heart of the mission to the Israelite Samaritans in spite of his early anti-Samaritan stand (Luke 9:52-55):

“And he followed Philip everywhere, astonished by the great signs and miracles he saw. When the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had accepted the word of God, they sent Peter and John to them.” (Acts 8:9-14)

In John 4, Jesus encounters a Samaritan woman. The chapter begins by specifying, “Jesus had to go through Samaria” (Jn. 4.1). When His disciples returned from the Samaritan village, he told them the source of his supernatural strength. His strength comes from doing God’s will by being part of His final harvest-gathering activity:

Look around you! Vast fields are ripening all around us and are ready now for the harvest. ” (Jn. 4:35).

While in Samaritan territories, Jesus pointed out that the disciples needed to think outside the box and include “heretical” Israelite Samaritans in their vision for spiritual harvesting. Jesus rightly claimed that the harvest was ready to be reaped. He was referring to the apostles and their future mission to the Samaritans in particular, and by extension to all nations of the world. Both ideological locations (“Heretical and Adversarial Samaritans” and “Gentile nations”) were not natural places for Israelite Jewish disciples of Jesus to look for a spiritual harvest.

To receive more information about learning Biblical Languages with Hebrew University of Jerusalem/eTeacher Biblical program online at affordable cost, please, click here.

© By Eli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg, Ph.D.

To sign up for weekly posts by Dr. Eli, please, click here. It is recommend by Dr. Eli that you read everything from the begining in his study of John. You can do so by clicking here – “Samaritan-Jewish Commentary”.

I would disagree with the assumption that John was not of Jewish origin. It was originally called Signs or Omet which is to view his miracles and the usage of Jews is confusing but to claim that it was for Samaritans and had no place in the synagogue is mere assumption. History tells us that John was the Gospel of the Jewish Christians and not the Gentiles. The Christians that lived in Jerusalem used this Gospel they called Omet to prove that he was their long awaited Messiah. I believe that the councils of 4th century blurred the lines and made a fake parting and the modern adherents of these schools of thought blur the lines to alienate the Jewish Christians. There is huge hate from both sides against the thought that their was Jewish Christians. Also using the book of Acts( a book written by Female Platonists not in the beginning but after the completion of the book of Luke) is not sufficient evidence or proof. Especially when we go over the false information that is given in Acts that was put in through later redaction. For instance Acts teaches us that Judas burst asunder and was punished by God or an Angel of God but not the Devil tempting him to take his own life. The many overlooked facts of Luke and Acts that contradict History tells me that I can not put them side by side. Why did you not use Jude or James or possible some other sources to compare it with. As we know from Romans and Galaitians Paul was the one who gave the gentile Gospel that came from his Mediator Jesus Christ and Jesus Christ only. Also another misconception is that James played no role as leader of the early Christians. The first real Arch-Bishop according to history and not tradition(Orthadox or Catholic) was James. When everyone had a problem with the communities they went to James not Paul and not Peter It was not until the 4th Century that Byzantine was moved to Rome and succession was believed to be from Peter and Paul. All I am saying that using Acts as a reliable source until Acts can be proven to have been written before 4th century is not very scientific. Of all the Manuscripts found to date John is in every document whereas Luke was a Gospel used by Marcion and the only Gospel fit for use in his mind. But when God, who set me apart from my mother’s womb and called me by his grace, was pleased 16 to reveal his Son in me so that I might preach him among the Gentiles, my immediate response was not to consult any human being. 17 I did not go up to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before I was, but I went into Arabia. Later I returned to Damascus Gal 1:15 so the one who brought the Gospel to the Gentiles was Paul not Peter or John and Paul’s Gospel was mediated to him by Christ. These false traditions are just that they have no teeth. Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Cephas[b] and stayed with him fifteen days. 19 I saw none of the other apostles—only James, the Lord’s brother. 20 I assure you before God that what I am writing you is no lie.

21 Then I went to Syria and Cilicia. 22 I was personally unknown to the churches of Judea that are in Christ. 23 They only heard the report: “The man who formerly persecuted us is now preaching the faith he once tried to destroy.” 24 And they praised God because of me. (Ibid) I understand that you seem to think that Pharisaic Jews were the only ones living in Jerusalem but the real argument between Jesus was not Jewish law but Babylonian traditions that had nothing to do with Gods law only traditions brought back to Jerusalem. So we all learn together and keep up the Good work.

Dear Chris, I read your comment. I am so sorry your comment has too many points that I simply can not address now. It will take too long to do the justice to everything here that needs response. From my stand point it is full of mistakes as I am sure you find my line of thinking to have those as well :-). I truly wish you well on your faith journey. Dr. Eli

May I just add a further thought. A devout woman once told me that she did not like the idea of “The Disciple that Jesus Loved” because she understood this as Jesus loving this person more than others. But the understanding should not be this. Rather the Disciple that Jesus Loved KNEW that Jesus loved him. May it be so for all of us till we are One with Him.

Well… 🙂 May I differ with you on this? I think (and I don’t think there is any doubt about it) that God loves his children equally meaning all the way. He can not love more than he already does. BUT on the human level people (and Jesus other than being God was also human) was indeed closer to some apostles. For example it is Peter, James and John that Jesus usually took to places he did not take the others. Now… if that is so… than could he not also feel closer to one of those three?!

I would caution you against making an association between the author of the Fourth Gospel, the disciple that Jesus loved, and the Apostle John.

Primarily textually, what is there in the Gospel that ties the two together. Nothing that I can see and much that, though not conclusive, gives you pause for thought.

The only mention of the Apostle John is in the Epilogue – “the sons of Zebedee and two others of his disciples” (Jn 21.2). The disciple that Jesus loves soon comes into the text. It does not seem to me that expressed this way that he is one of the sons of Zebedee. Whatever may have been the case later, we know in the other Gospels how these sons of Boanerges tended to behave during Jesus’s lifeetime. Can you see one of them happy to have seen the other in Jesus’s ‘kolpos’ (Jn13.23 resonating with Jn 1.18).

Many of tried to associate the disciple that Jesus loved with the “other disciple” in various places. I think this is understandable. This disciple was known to the Chief Priest (Jn 18.15). At the very least there is an important and brave disciple connected with ‘hoi Ioudaioi’. The Gospel author mentions such detail as the Chief Priests servant, Malchus ( Jn 18.10). When Peter and John in Acts do come before such people they are called ‘ agrammatoi’ and ‘idiwtai’ (Acts 4 13).

This leads to the question of how was Lazarus (Heb Eleazar) and his family. ‘ Many of hoi Ioudaioi who had come with Mary and seen what he (Jesus) had done believed in him’ which brings us to Caiaphas and his decision (Jn 11.45 +). Was Eleazar naturally part of this High Priestly elite. Was ‘the other disciple’ a young scion of this family ? There is also the debate on Polycrates’ evidence of John, the Presbyter at Ephesus, who wore the ‘pelaton’.

Apart from these specifics, and perhaps more importantly, the realisation that this Gospel’s theology is so immersed in the detailed Jewish theology of the time that is transformed. The Targumic theology is probably highly associated with the Temple and Temple worship and may be one reason why it all but disappeared after 70 AD. If you have not read Robert Hayward’s ” Divine Name and Presence; The Memra” which hardly mentions the Gospel but there is much here which enriches an understanding of the nature of John’s transformation, I do encourage you to do so. Hayward studied under Geza Vermes.

At the Cross, there is only the women and the disciple that Jesus loved mentioned. The rest have fled. (One of the twins there ?). And then Jesus’s words to this disciple “Behold your mother ‘kai ap ekeinHs tHs wras’ (and from that very hour) he took her to his own home”. Not conclusive I know and ‘hour’ can mean various things in John but that ‘ekeivHs’ is strong. Perfectly possibly if the disciple takes her to Bethany – but not Galilee.

And then this young man running with Peter on Easter Morning (Jn 20). Only one of the twins ?

If the first words of Jesus in the Gospel were to Andrew ‘and the other disciple’ – “What do you want?” and they say “Where are you staying – ‘GK menw’ and Jesus replies “Come and you will see !” (Staying/abiding and seeing all critical John words), Jesus’s final words are to Peter regarding the disciple that Jesus loved. It is all in the context of them now about to do different things and have different futures and to paraphase ‘ If I want you to do this and someone else to do that’ “What is that to you ?” (Jn 21.20 and Jn 21.23). If only the Christian Church in the last 2000 years had taken this to heart.

The Disciple whom Jesus Loved is the perfect Witness who always stays in the background – the one who understand Jesus when others do not perhaps because he like John the Baptist knew “He must become greater, I must become less” (Jn 3.30). Is his signature then in the text ?

Well possibly – and although I said I would not mention gematria again – and please don’t make this your reply – I mentioned before that Hebrew gematria seems to fit Jn 21. It has been pointed out that John in the first century was often written in Hebrew ‘Yehohanan’. This has a gematria of 129. Off you trot to the 129th word in Jn 21. You find it is simply ‘ho’. Disappointing, until you realise that it is the “The” in “The Disciple that Jesus Loved”. I remember tears coming to my eyes the first time I read this.

I suppose I should finish by saying – I am enriched by your work but please don’t push the undoubtedly important Samaritan agenda to the point where you are making associations with John the Apostle which I do not think can be justified as regards the extraordinary text of this Gospel. Thank you.

Paul, hi. In the future do try to make your comments way shorter (I normally don’t approve such a long comments), but I did this one. When I have time I will reply to your points. Let us keep thinking about it. By the way for the record I am not convinced that John wrote it, but for the readers benefit I provide a good discussion on pros and cons:

https://bible.org/seriespage/background-study-john

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I believe that you should publish more on this subject matter,

it might not be a taboo subject but typically folks don’t talk about such subjects. To the next! Kind regards!!

Dear Ellen, the subject of Samaritan studies is not at all taboo. There are number of important studies that are now addressing the issue. I think the time when Samaritan studies and New Testament studies were divorced one from another is finally over.

IF the Gospel of ‘John’ was written to the Israelite Samaritans; could it have been written in Hebrew/Aramean first? There seem to be a large number of ‘Hebrewisms’ throughout this gospel? I believe that several of the Gospels were written in Hebrew, originally. Matthew, Mark, ‘John’, and Luke/Acts, I feel were all written in Hebrew for dispersal first, as they were written for a Hebrew audience.

It could, but there is no evidence for it that is convincing. Hebraisms do not mean more than Greek of John was thought in “immigrant” Jewish Greek with Semitic thought patterns. “Roman Palestine” was thoroughly Hellenized. For example Tamlud Yerushalmi is full of Hellenized material. So, the language of composition can give us less than we need/want.

The following Bishop John Lightfoot’s discussion the Jewish authorship of the Gospel. (From the essay “Internal Evidence for the Authenticity and Genuineness of Saint John’s Gospel,” published in his Biblical Essays (London: Macmillan, 1893), pp. 144-46.)

First of all, then, the writer was a Jew. This might be inferred from a very high degree of probability from his Greek style alone. It is not ungrammatical Greek, but it is distinctly Greek of one long accustomed to think and speak through the medium of another language. The Greek language is singularly high in its capabilities of syntactic construction, and it is also well furnished with various connecting particles. The two languages with which a Jew of Palestine would be most familiar — the Hebrew, which was the language of the sacred Scriptures, and the Aramaic, which was the medium of communication in daily life — being closely allied to each other, stand in direct contrast to the Greek in this respect. There is comparative poverty of inflections, and there is an extreme paucity of connecting and relative particles. Hence in Hebrew and Aramaic there is little or no syntax, properly so called.

Tested by his style, then, the writer was a Jew. Of all the New Testament writings the Fourth Gospel is the most distinctly Hebraic in this respect. The Hebrew simplicity of diction will at once strike the reader. There is an entire absence of periods, for which the Greek language affords such facility. The sentences are coordinated, not subordinated. The classes are strung together, like beads on a string. The very monotony of the arrangement, though singularly impressive, is wholly unlike the Greek style of the age.

More especially does the influence of the Hebrew appear in the connecting particles. In this language the single connecting particle waw is used equally, whether co-ordination or opposition is implied; in other words, it represents “but” as well as “and.” The Authorized Version does not adequately represent this fact, for our translators have exercised considerable license in varying the renderings: “then,” “moreover,” “and,” “but,” etc. Now it is a noticeable fact that in Saint John’s Gospel the capabilities of the Greek language in this respect are most commonly neglected; the writers falls back on the simple “and” of Hebrew diction, using it even where we should expect to find an adversative particle. Thus v. 39, 40, “Ye search the Scriptures, for in them ye think ye have eternal life : and they are they which testify of Me: and ye will not come to me”; vii. 19, “Did not Moses give give you the law, and none of you keepeth the law?” where our English version has instead an adversative particle to assist the sense, “and yet”; vii. 30, “Then they sought to take Him: and no man laid hands on Him,” where the English version substitutes “but no man”; vii. 33, “Then said Jesus unto them, Yet a little while am I with you, and I go to Him that sent Me,” where again our translator attempts to improve the sense by reading “and then.” And instances might be multiplied.

The Hebrew character of the diction, moreover, shows itself in other ways,– by the parallelism of the sentences, by the repetition of the same words in different clauses, by the order of the words, by the syntactical constructions, and by individual expressions. Indeed, so completely is this character maintained throughout that there is hardly a sentence which might not be translated literally into Hebrew or Aramaic without any violence to the language or to the sense.

I might point also to the interpretations of the Aramaic words, as Cephas, Gabatha, Golgotha, Messias, Rabboni, Siloam, Thomas, as indicating knowledge of the language. On such isolated phenomena, however, no great stress can fairly be laid, because such interpretations do not necessarily require an extensive acquaintance with the language; and, when the whole cast and coloring of the diction can be put in evidence, an individual word here and there is valueless in comparison.

… If, therefore, we had no other evidence that the language, we might with confidence affirm that this Gospel was not written either by a Gentile or by a Hellenistic Christian, but by a Hebrew accustomed to speak the language of his fathers.

[…] to Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. At one point, together with Peter, he engaged in a Judean Jesus Mission to Israelite Samaritans (Acts 8:9-14). This will become an important connection in the future. Though John is not […]

excellent we need to know the origin our faith