If you have ever been to Israel, you have most likely visited the most famous Jewish religious site in Jerusalem: the Western Wall. You are probably aware that this wall is but a small section of the massive retaining structure that once held up the esplanade of the Herodian Temple. But you are probably not aware that the Western Wall prayer plaza is covering an ancient Roman street known by archaeologists as the Eastern Cardo. The ancient paving stones seen in the picture below are built directly in the Jerusalem’s central valley, which separates the Temple Mount to the east from the Jewish Quarter to the west.

This valley is usually known by a rather odd name: the Tyropoeon Valley. In book five of his famous work The Jewish War, the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius begins his description of the fighting in the city of Jerusalem with a geographical survey of the city:

The city was built upon two hills, which are opposite to one another, and have a valley to divide them; at which valley the corresponding rows of houses on both hills end. Of these hills, that which contains the upper city is much higher, and in length more direct…Now the Valley of the Cheesemakers, as it was called, and was that which we told you before distinguished the hill of the upper city from that of the lower, extended as far as Siloam. (BJ V.136,140)

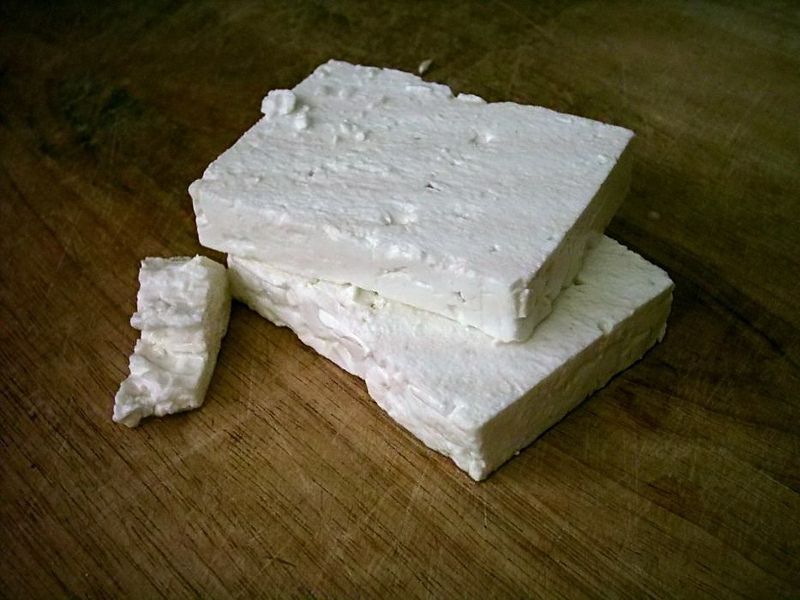

In the original Greek text written by Josephus, the name “cheese-makers” or “cheese-mongers” is tyropoeon (τυροποιῶν) formed from two Greek words tyros (τυρός) meaning “cheese” and poieo (ποιέω) meaning “to make, produce, create.” What exactly is this name referring to? Was Jerusalem a hub of cheese production in ancient times? Let’s find out!

First some geographical background. As we already explored in another blog post, the Tyropoeon Valley bisects Jerusalem’s Old City, separating the lower eastern ridge (Mount Moriah) from its higher western counterpart (the Upper City). This central valley was the commercial heart of Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period, as can be seen from the impressive remains of shops which have been excavated south of the Western Wall, beneath Robinson’s Arch.

The valley begins outside the Old City in the vicinity of the Musrara neighborhood, running southeast toward the walls of the Old City and entering the Damascus Gate. At this point, it turns due south and cuts directly through the Muslim Quarter all the way to the Dung Gate. It skirts the eastern side of the City of David, eventually joining the Kidron Valley, which runs down to the Dead Sea.

Today, the Tyropoeon Valley is hardly recognizable. Unlike the impressive Kidron and Ben Hinnom Valleys which circumscribe the Old City, there is little to be seen of the humble Cheesemaker’s Valley. Over the centuries it has become almost completely filled in with debris and buildings. In the Ayyubid and Mameluk periods many homes and public institutions (i.e., mosques and madrasas) were built upon vaults that spanned the valley in order to be as close as possible to the Haram al-Sharif.

These massive constructions made it possible to access the Temple Mount by means of numerous east-west streets (e.g., Suq el-Qattanin, Tariq Bab el-Silsila) without ascending almost any stairs. So where is the Tyropoeon today? It mostly runs deep beneath the main north-south artery of the the Muslim Quarter that runs from Damascus Gate to the Western Wall Plaza. The name of the street – Tariq Al-Wad / Rehov HaGai (= The valley street) – preserves a memory of the original topography of the city.

Unfortunately, Josephus does not explain his use of the term “cheese-makers” and it is not corroborated in any contemporaneous texts. There is no evidence whatsoever that cheese – let alone any particular food – was manufactured in this part – or in any part – of the city. Its meaning has puzzled generations of scholars. One convincing theory has been offered by the eminent Jerusalem archaeologist Dan Bahat. He thinks that the original name was the “Valley of the Silversmiths,” which makes sense given the archaeological evidence for commercial activity here. In Hebrew this would have been Emek HaTzorfim עמק הצורפים. Transliterated into Greek, the word Tzorfim צורפים became Tyropim (τυροπίμ) which has no meaning whatsoever in Greek. Later, a copyist altered the meaningless word Tyropim to Tyropoeon (τυροποιῶν) which means “cheese-makers”. This is a far more picturesque name for Greek audiences and it has stuck to the present day.

Another theory is that the valley was originally called the “Valley of Decision” (Emek HeHarutz עֵמֶק הֶחָרוּץ) which is mentioned in Joel 3:14. Most commentators assume that in this verse Joel is referring to the Kidron Valley, given that he mentions the Valley of Jehoshaphat earlier in Joel 3:2. But maybe Joel is in fact referring to two separate valleys where future judgment will be dispensed. Joel’s use of the word harutz (“decision”) must be related to Daniel’s use of the same term to mean “trench” (Daniel 9:25). According to this theory, if the term Emek HeHarutz was originally a reference to the central valley, it would have changed its name slightly over time to Emek HaHaritz. That is, the word harutz (חרוץ) which means “a strict decision” shifted slightly to haritz (חריץ) which means “a thing cut with a sharp instrument”, as seen in 1 Samuel 17:18. Although it is not entirely clear what exactly Jesse is asking David to bring to the battlefield in this verse, the Hebrew term haritzei hehalav חֲרִצֵי הֶחָלָב indicates some type of dairy food item that has been cut with sharp tool. Cheese is not a bad guess. Both words (harutz and haritz) come from the same root HRZ חרץ which has to do with sharpness. Presumably, God’s judgment is meted out with sharp decisiveness, just as slices of cheese are cut with a sharp instrument. At the time when Josephus was living in Jerusalem, the central valley was commonly referred to as Emek HeHaritz. Although native Hebrew speakers (like Josephus) would have understood this to mean “the valley that is sharply cut”, non-native speakers (such as the Roman scribal assistants that helped translate Josephus’ words into Greek) misinterpreted it to mean the “valley of the sliced cheese.” This is the source of the Greek name Tyropoeon.

I would like to present two alternative theories of my own. The first is that the original name of the valley was the “Valley of the Tyrians.” The Phoenician city of Tyre, located just 40 km north of the Israeli coastal city of Akko, was the most important trading hub in the eastern Mediterranean basin. The Bible makes many references to the trading activities of the Tyrians. For example, King Hiram of Tyre sent workers as well as precious wood from the cedar forests of Lebanon to Jerusalem in order to build David’s palace and Solomon’s Temple (2 Sam. 5:11, 2 Chr. 2:3). The prophet Ezekiel laments the destruction of Tyre in a long chapter that includes numerous references to exotic lands that flocked to this trading city (Ezekiel 27:1-36). This valley became the main commercial marketplace in Second Temple Jerusalem, something indicated clearly in the archaeological record. The Tosefta’s reference to the “lower marketplace” (השוק התחתון) might preserve a memory of this area as well (t. San 14:14). Moreover, the Tyrians were deeply involved in the commercial activity surrounding the Temple. It is well-known that the Tyrian tetradrachma was the standard coin accepted by the priestly authorities to pay the half-shekel Temple tax. I would like to suggest that this because this valley was commercial and the city of Tyre was synonymous with trade, the name Tyrian became the label of choice.

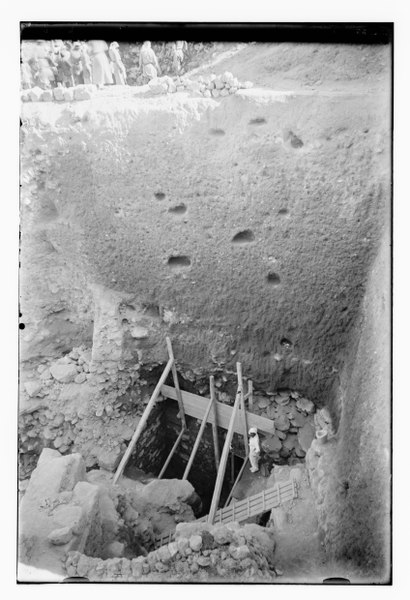

My second theory is the original name of the valley comes from the Hebrew word תורפה torpah. This word can refer either to a “dirty place” (including one’s private parts) or to a “weak place.” Jerusalem’s central valley fulfills both of these criteria. It was dirty, owing to the fact that for centuries most of ancient Jerusalem’s garbage was thrown here, causing the valley to fill up significantly. The image below shows how much soil and debris accumulated in this valley, requiring much deeper archaeological excavations than in almost any other place in Jerusalem. In addition, the central valley gets its start at the weak northern flank of the city, located in the vicinity of today’s Damascus Gate. The Babylonian Talmud, for example, contains an interesting discussion of why the “upper pond” in Jerusalem was not consecrated. The answer given is that:

Because it was a weak point of Jerusalem and it would have been easy to conquer the city from there, it became necessary to include it within the wall. מפני שתורפה של ירושלים היתה ונוחה היא ליכבש משם (Shevuot 16a)

The Hebrew name Torpah was transliterated as τυρπα in Greek which eventually morphed into two words tyro τυρο and poion ποιων as the text was copied over the centuries.

All four of these explanations are just theories, trying to explain the source of the rather odd name “the Valley of the Cheese-makers.” I would love to hear if you find any one of them more convincing than the others. As always, thanks for reading!

Join the conversation (No comments yet)