In the first half of chapter 7 of the Gospel of Mark Jesus gets into a heated argument with a group of Pharisees and scribes from Jerusalem regarding the issue of hand-washing prior to eating. Mark tells us that Jesus and his disciples were eating with “defiled hands”, whereas the “the Pharisees, and all the Jews, do not eat unless they thoroughly wash their hands” (Mark 7:3). What is going on here? Is it possible that Jesus ate with dirty hands?

The hand-washing referred to in Mark 7 is not hygienic hand-washing for the purpose of cleanliness. We can assume that if his hands were indeed dirty, Jesus would have washed them! Rather, this a ritual purification of the hands before a meal, somewhat analogous to the priest’s purification of his hands prior to performing a sacrifice, as described in Exodus 30:20:

When [Aaron and his sons] go into the tent of meeting, or when they come near the altar to minister, to make an offering by fire to the Lord, they shall wash with water (יִרְחֲצוּ-מַיִם) so that they may not die.

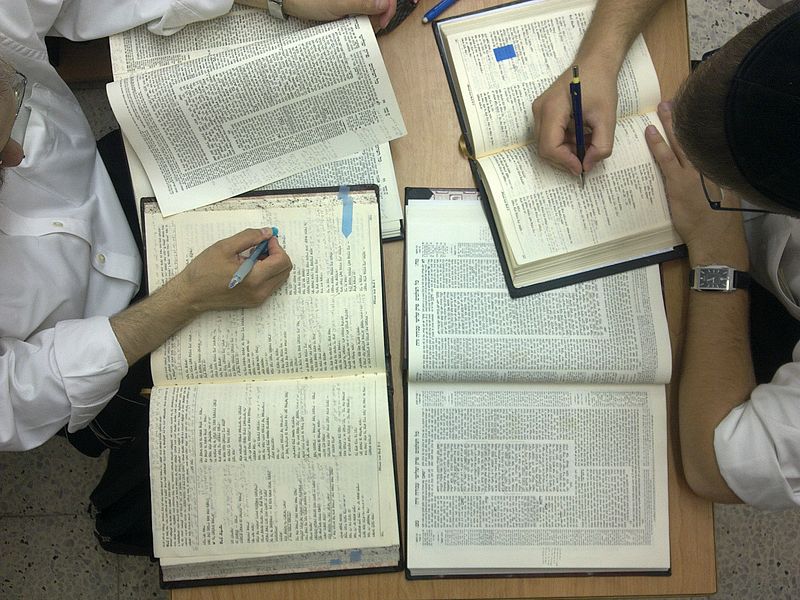

The Pharisees did not serve as priests in the Temple, as this was mainly the domain of the Sadducees. The innovative ritual described here represents a Pharisaic attempt to bring the ceremonial standards of the Temple into the home. The radical implication is that every meal is like a sacrificial meal in Jerusalem. In Hebrew this practice is called נטילת ידים netilath-yadayim, meaning “lifting up the hands” and it is still practiced today by Jews before eating a substantial meal, that is, a meal which contains bread.

A Hasidic man washed his hands with a washing cup prior to praying at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. The same ritual is performed prior to eating bread.

Why is this type of innovative ritual unacceptable to Jesus? The key phrase here is “tradition of the elders” (Greek: παράδοσιν τῶν πρεσβυτέρων), meaning the Oral Law. This practice is not commanded in the Torah. It is a Pharisaic supplement, which would later be written down and come to be called the Mishnah. Interestingly, the word “tradition” appears five times in this passage! The word in Greek is παράδοσις paradosis, meaning “something that is handed down”.

But Jesus is not only bothered by the fact that the Pharisees have elevated the “tradition of the elders” to the same status as the Written Law. He is bothered by the dishonest methods they use. In the continuation of the passage he quotes Isaiah 29:13:

This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me; in vain do they worship me,teaching human precepts as doctrines.’

Like Isaiah, Jesus stresses that inner spiritual purity is more important than outer ritual purity. Jesus’ central criticism of the Pharisees is that they are “hypocrites” (ὑποκριτῶν, Mark 7:6), that is they use legal loopholes in the Oral Law in order to serve their own needs. Here is the example that Jesus provides to illustrate his point:

9 Then he said to them, “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition! 10 For Moses said, ‘Honor your father and your mother’; and, ‘Whoever speaks evil of father or mother must surely die.’ 11 But you say that if anyone tells father or mother, ‘Whatever support you might have had from me is korban’ (that is, an offering to God)— 12 then you no longer permit doing anything for a father or mother, 13 thus making void the word of God through your tradition that you have handed on. And you do many things like this.”

The example that Jesus gives of a non-biblical Pharisaic tradition is a vow which allows someone to circumvent the Torah’s obligation to honor their parents. The word Jesus uses for such vow is korban. But as Mark adds in parenthesis, the word korban does not really mean “vow”, but “an offering to God”. Interestingly, in manuscripts of Mark, the word korban has been transliterated into Greek letters (κορβᾶν), although it is Hebrew, not Greek. Matthew does the same thing at the end of his Gospel in his narration of the death of Judas:

“But the chief priests, taking the pieces of silver, said, ‘It is not lawful to put them into the treasury, since they are blood money.’” (Matthew 27:6).

In the original Greek text of Matthew the word “treasury” is denoted by the word korbanas (κορβανᾶς), which is the Aramaic version of korban. Both korban and korbanas are examples of several Hebrew/Aramaic words that have been preserved by the Greek-speaking authors of the gospels rather than being translated. The most famous example is probably Jesus’ utterance on the cross in Matthew 27:46, which draws on Psalm 22:2: “My Lord, my Lord why have you abandoned me?” Matthew deemed the phrase to be so important that he left it in Aramaic rather than translating it into Greek:

Greek: Ἠλί, Ἠλί, λιμὰ σαβαχθανί

English: Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani

Aramaic: אלי אלי למה שבקתני

Let us take a closer look at the word korban. The Hebrew Bible contains many different words for various kinds of sacrifices, but it uses the word korban קרבן as a general term, as seen for example in Leviticus 1:2:

Speak to the people of Israel and say to them: When any of you bring an offering of livestock to the Lord, you shall bring your offering from the herd or from the flock.

In Hebrew, korban קרבן literally means “rapprochement” or “coming closer”. It derives from the root KRB קרב which means “to draw near”. In English, we tend to use the word “sacrifice” in the negative sense of “surrender”. It is to give up something of worth in order to serve a greater purpose. For example, “She worked long hours, sacrificing sleep for the welfare of her family.” It is the right thing to do, but it involves a punishing sense of loss. The Hebrew Bible sends a different message about the meaning of sacrifice. Surely it does not make sense that the God of Israel desires to inflict upon his chosen people such a burdensome feeling of defeat every time they come to worship him. The purpose of sacrifice is not to prove one’s faith by forfeiting something valuable, but to gain intimacy with God by bringing Him a cherished gift.

Join the conversation (No comments yet)