This coming Saturday night, Jews around the world will sit on the floors of their synagogues and read one of the saddest books in the entire Bible: the Book of Lamentations. For 25 hours – from sundown on Saturday to sundown on Sunday – they will not eat or drink anything. This is the grimmest day of the entire Jewish year: the ninth day of the month of Ab, or as it is called in Hebrew,Tisha b’Av. According to Jewish tradition, numerous tragic events in Jewish history took place on this very date, including the tragically negative assessment of the Promised Land brought back by the Twelve Spies (Numbers 13-14), the bloody beginnings of the First Crusade (1096 CE) and the expulsion of the Jews from England (1290 CE). Most famously, however, this date marks the destruction of both Jerusalem Temples. The First (Solomonic) Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians on this date in 586 BCE; the Second (Herodian) Temple was destroyed by the Romans on this same date in 70 CE. For the past 2000 years, Jews have marked this unfortunate date by devoting themselves to public rituals of mourning.

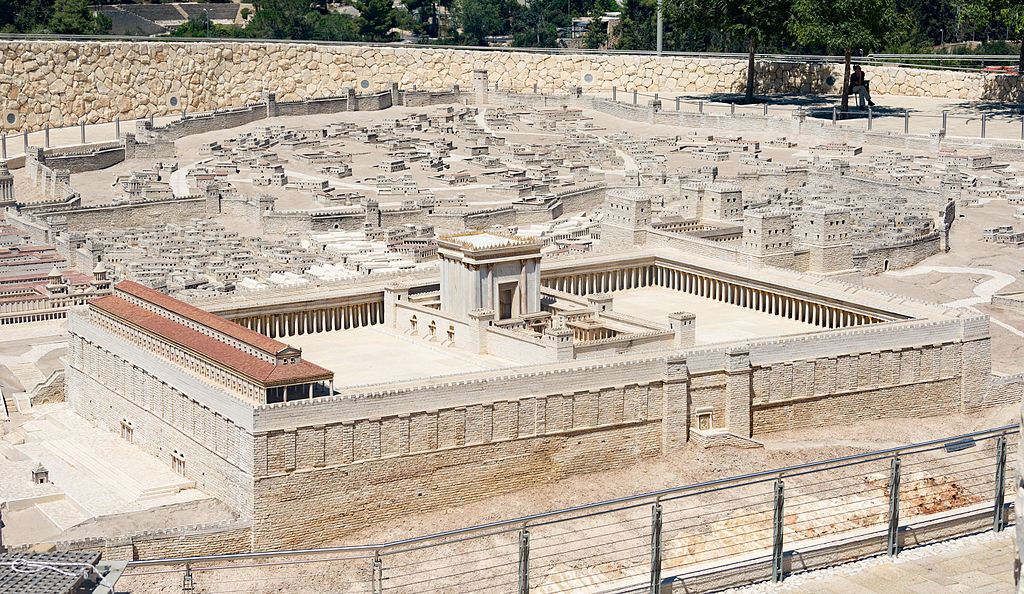

In this post, I want to take a closer look at the archaeological evidence for the destruction of the Second Temple. Despite the massive size of the Herodian Temple, it is not so easy to find remnants of this complex. This is largely due to the fact that the Israel Antiquities Authority does not have jurisdiction to conduct archaeological excavations upon the Temple Mount, which is owned by the Jordanian Waqf. So we need to look elsewhere, namely in the archaeological park at the base of the Temple Mount along the Western and Southern Walls. Here a very special stone that was pushed down from the Temple during the destruction of the year 70 CE. It contains a Hebrew inscription, making it a very rare archaeological vestige of daily life in the Temple before the events of 70.

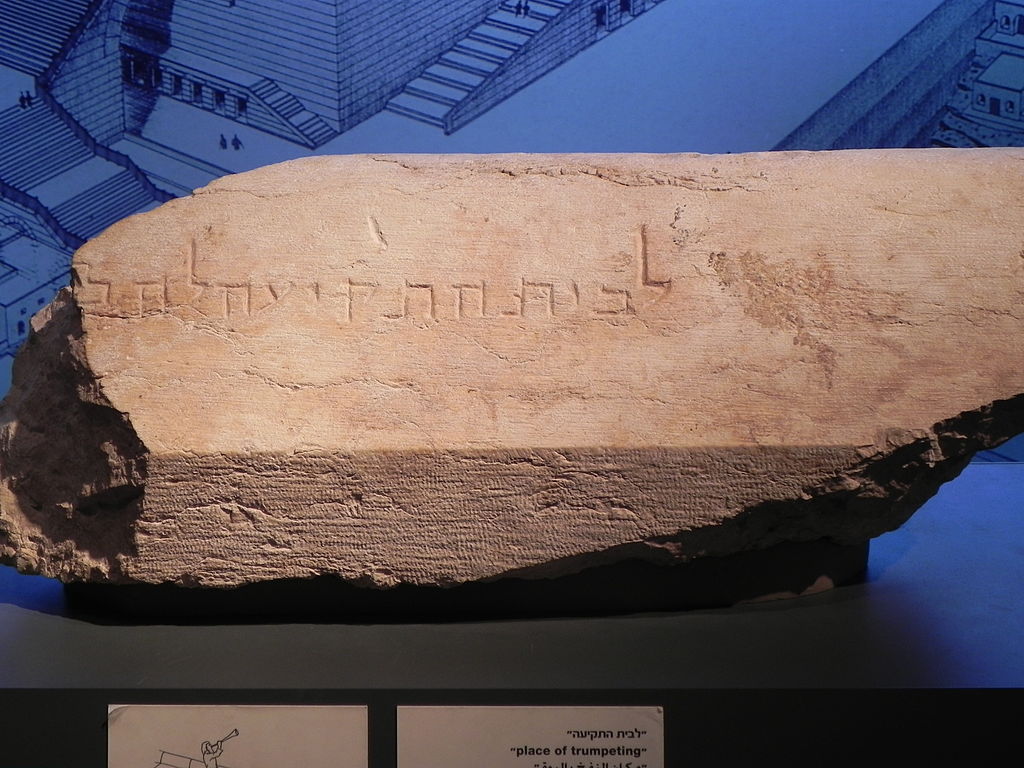

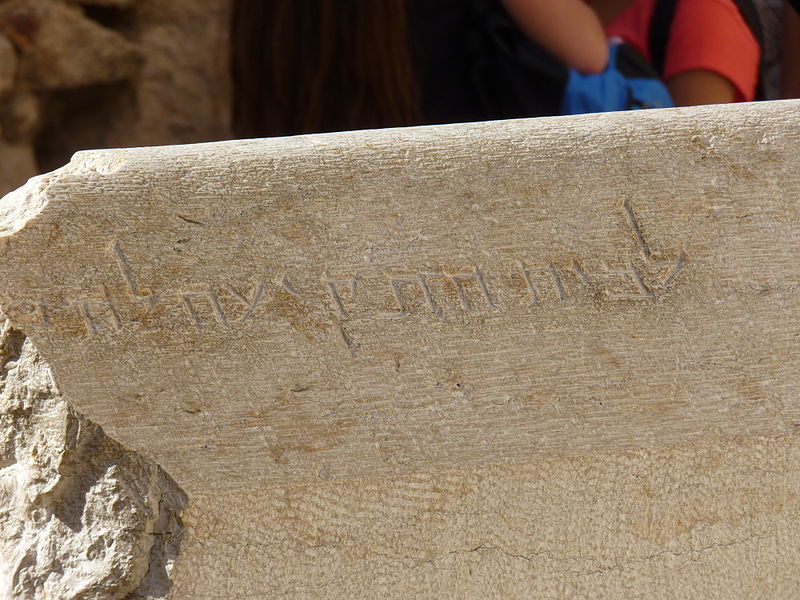

Digging along the Western Wall of the Temple Mount in the late 1960s, archaeologist Benjamin Mazar found many large Herodian stones that had been pushed down by the Romans during the destruction of the Temple. One stone, however. caught his eye because it had a very unique shape. Unlike most of the stones he uncovered in the area of Robinson’s Arch, this one is not merely a cube-shaped limestone building block. Instead, is shaped like an L and has a smooth rounded top reminiscent of a banister. Even more exciting, it bears one of the most famous Hebrew inscriptions ever found. It says:

…לבית התקיעה להב

le-beit ha-teqiah lehav…

Unfortunately, the stone broke when it was pushed down into the valley and the end of the inscription is cut off. Mazar suggested that the completed third word should read le-havdil (להבדיל) “to distinguish” or alternatively, le-hakhriz (להכריז) “to announce”. This variation is due to the fact that it is unclear whether the last preserved letter is a C (כ) or a B (ב). The two options would look like this:

לבית התקיעה להבדיל

“To the house of trumpeting to distinguish”

לבית התקיעה להכריז

“To the house of trumpeting to announce”

The “house (or place) of trumpeting” indicates the official location where a Temple priest would blow a trumpet (or perhaps a ram’s horn = shofar) to “announce” the beginning and end of the Sabbath and festivals. Thus, the meaning of the second suggested word – “to distinguish” – namely, to distinguish day from night, sacred from profane. This trumpet blast was a signal to the merchants in the marketplace below to close their shops, since business was forbidden on the Sabbath. The 1st century Jewish historian Josephus refers to this practice in passing in his description of Simon of Gerasa’s capture of Jerusalem:

But having the advantage of situation, and having withal erected four very large towers aforehand, that their darts might come from higher places, one at the north east corner of the court, one above the Xystus; the third at another corner, over against the lower city; and the last was erected above the top of the Pastophoria where one of the priests stood of course, and gave a signal beforehand, with a trumpet at the beginning of every seventh day, in the evening twilight: as also at the evening, when that day was finished: as giving notice to the people when they were to leave off work, and when they were to go to work again. (Josephus, The Jewish War 5.9.12)

Given the location where it was discovered, this stone was presumably originally part of the southwestern corner of the portico which surrounded the Second Temple, as seen on the left-hand side of the photograph above. It was pushed down into the Tyropoeon Valley during the Roman destruction in the year 70 AD and soon covered over with debris that preserved it for 2000 years. Because archaeologists have never been able to dig on the Temple Mount itself, this is one of the only tangible remnants we have of the Temple. Fascinatingly, these ancient words are still relevant today. In modern Jerusalem, every Friday afternoon a siren still signals the beginning of the Sabbath. And the Hebrew word teqiah is the same word today used in modern Hebrew to refer to blowing a shofar.

Join the conversation (No comments yet)