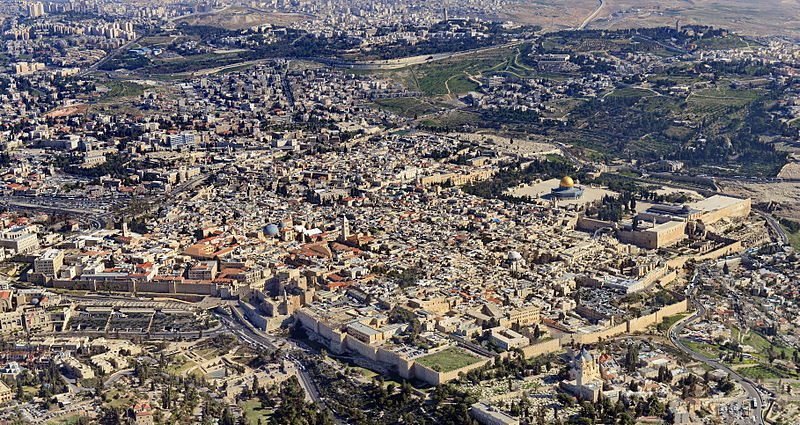

Aerial view of Jerusalem’s Old City (center) and the Mount of Olives (right). During his final week, Jesus would walk daily from Bethany on the backside of the Mount of Olives into the Temple. Image courtesy of Avram Graicer, wikimedia

The account of Jesus’ giving of the “sign of Jonah” is found in two of the four gospels (Matthew 12:38-42 and Luke 11:29-32) with an important difference. In both versions of the story Jesus is angered by the crowd’s request for a “sign” (σημεῖον) to prove his legitimacy. Previously when crowds had asked Jesus to perform acts of healing, he was willing. But this request is humiliating. The crowds simply want to be wowed by a magic trick. This is not the only time Jesus encountered such a request during his ministry. In John’s gospel the crowds ask Jesus: “What sign are you going to give us then, so that we may see it and believe you?” (John 6:30). The apostle Paul would later write that “Jews demand signs” (1 Corinthians 1:22). Jesus objects strongly to this demand. He does not want to be regarded merely as a magician. So he lashes out at the crowd and tells them that his “sign” will be to act as the prophet Jonah did. Both Matthew and Luke make the analogy between Jesus and Jonah, but they express this comparison differently. Luke says “for just as Jonah became a sign to the people of Nineveh, so the Son of Man will be to this generation” (Luke 11:30). In other words, it is Jonah’s moral exhortation which bears resemblance to the teachings of Jesus. Matthew has a different take: “For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the sea monster, so for three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth.” (Matthew 12:40 NRSV). In other words, it is Jonah’s miraculous revival from near death which links him to the future resurrection of Jesus.

Many readers are troubled by Matthew’s statement because it seems to stand at odds with the chronology of the Passion narrative found at the end of the gospels. The “Sign of Jonah” passage in Matthew seems to suggest that Jesus will need to be in the tomb for three whole days and three whole nights. But we know that Jesus was entombed for approximately 35 hours, from Friday evening (“when evening had come and since it was the day of Preparation, that is the day before the Sabbath,” Mark 15:42) to Sunday morning (“very early on the first day of the week” Mark 16:2). This is hardly a day and a half. Biblical commentators have offered various solutions to explain this apparent contradiction. Matthew’s “three days and three nights” has been interpreted figuratively to mean a long enough time to ensure that one is indeed dead. Another approach has been to move the day of the crucifixion back to Thursday in order to allow for three full days in the tomb. Others wish to understand the number “three” in the loose sense of part of three individual days: Friday night, Saturday and Sunday morning. Still others have argued that Matthew has a widespread tendency to use the number three throughout his gospel (see 13:33; 15:32; 17:4; 26:34; 27:40), and we should not try to reconcile this with the burial of Jesus at all costs. All of these approaches have their drawbacks, and so I would like to offer an alternative reading of Matthew 12:40 here.

A statue of Jonah in the belly of the fish used in the Good Friday procession in Lohr am Main (Bavaria, Germany).

I think the main problem is that most interpreters of this verse have focused their exegetical energy on the phrase “three days and three nights”. In my opinion, the key is to focus instead on the phrase “in the heart of the earth”. All English translations render this phrase identically, leading everyone to assume that Jesus is referring to the period of his entombment. But if we look at the original Greek text of Matthew we find that is says: ἐν τῇ καρδίᾳ τῆς γῆς (en tē kardia tēs gēs). This could just as easily be translated “in the heart of the land”. The Greek noun γῆ (gē) has a broad range of meanings, from the most abstract (“earth”) to the most concrete (“soil”). Included in this broad semantic range is the English word “land”, which is the usual translation of the original Hebrew term that Jesus himself would have used: ארץ (eretz). In the mouths of biblical prophets, the word eretz almost always has a specific territorial meaning: the Land of Israel. Following the work of Robert Wilken, I think it makes a lot of sense to view Jesus not merely as an eschatological figure, but as a restorationist prophet who was looking forward to the end of Roman rule in the land, meaning the land promised to Abraham by God. Wilken, for example, suggests that when Jesus uses the word gē in the famous beatitude “blessed are the meek for they shall inherit the earth”, we really should translate this “blessed are the meek for they shall possess the land,” which echoes the language of Psalm 37:11 (The Land Called Holy, 48).

The Mount of the Beatitudes, the traditional location of the Sermon on the Mount, just above the fishing village of Capernaum where Jesus based his Galilean ministry.

How does this alternative translation of Matthew 12:40 (“in the heart of the land”) clear things up? Let’s back up and have a look at Jesus’ final week in Jerusalem. For the majority of the week, Jesus followed a fixed routine. Each day he would make his way into the city of Jerusalem from the village of Bethany, on the eastern side of the Mount of Olives, where he was staying in the house of Mary, Martha and Lazarus. He would spend the day teaching in the porticoes surrounding the Temple (Luke 19:47; John 10:23), and at the end of the day he would return to Bethany (Mark 11:11; Luke 21:37-38). This journey of two miles in each direction was inconvenient but necessary because Jesus did not want to risk being arrested at night within the city. Jesus had become enormously popular among the masses, but his anti-establishment message was regarded as dangerous in the eyes of the Temple priesthood. So long as he was surrounded by large crowds during the daytime, he was safe. But he feared that the authorities would snatch him in the middle of the night to avoid a public outcry. So he made sure to leave the city each evening. On Thursday of this week, his routine was broken. It was the eve of Passover, and the pre-festival preparations reached a climax. The day began as usual with Jesus entering the city, but it would end very differently. Rather than returning home to Bethany at the end of the day, Jesus ate the Last Supper in the “upper room” of a house within the city. Late that night, he departed for Bethany as usual, but he never made it home. Feeling anxious, he stopped to pray in Gethsemane at the foot of the Mount of Olives. It is here that he was apprehended by the Temple guards and taken to be interrogated by the high priest Caiaphas. From this point on in his earthly life, Jesus would not leave the city. Over the next two days he would be tried, convicted, scourged, crucified and buried – all within the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem.

I wish to argue that the phrase “the heart of the land” is actually referring to Jerusalem rather than to the tomb (“in the heart of the earth”). In this metaphor, the land is a body and Jerusalem is its pulsing heart. A slightly altered version of this metaphor is found in Jeremiah, where the body is Jerusalem and the Temple is the heart:

O Jerusalem, wash your heart clean of wickedness

so that you may be saved.

How long shall your evil schemes

lodge within you? (Jeremiah 4:14)

Jesus spent an entire week (Sunday to Sunday) in the greater Jerusalem region, entering the city each day but departing each evening. Within the framework of this week, he spent three whole consecutive days (Thursday, Friday, Saturday) within the confines of Jerusalem itself. For three whole days Jesus was not outside the boundaries of the city, also known as the distance one was permitted to travel on the Sabbath (cf. Acts 1:12). Rather he was in the “heart of the land”. By Sunday morning he had already left town. The sign of Jonah, according to Matthew’s telling, therefore refers to the entire Passion narrative, not merely the burial and resurrection from the tomb.

Thanks Jonathan – thought provoking blog.

The lateral thinking on the ‘3 days in the heart of the land’ is worth considering further.

However, 2 points were prompted by your article:

1. Luke 11.30 say Jonah ‘became’ (egeneto) a sign, so Jesus will. I am not sure Jonah’s preaching would have counted as a sign? More the evidence that he had endured a remarkable ‘resurrection’ from being entombed in a great fish?

2. Matt 12.40 – again the word ‘sign’ seems to me to be significant (if that is not a pun!). How would Jesus being in Jerusalem for 3 days be a sign? The wording is very defined also: ‘just as Jonah was IN THE BELLY of the sea monster three days and three nights, so the Son of Man will be IN THE HEART of the land/earth three days and three nights.’ The words do suggest the same metaphor of ‘down into’ for both signs?

Anyway, your new thought is also true, whether or not it was the specific meaning Jesus was referring to here.

Thank you.